Uzbekistan and Principles for Responsible Asset Return

Dr Kristian Lasslett, ‘Principles for responsible asset return’, paper presented to Grand corruption and recovery of stolen assets: What does Ukraine need to finally succeed?, Transparency International, 22 May 2017.

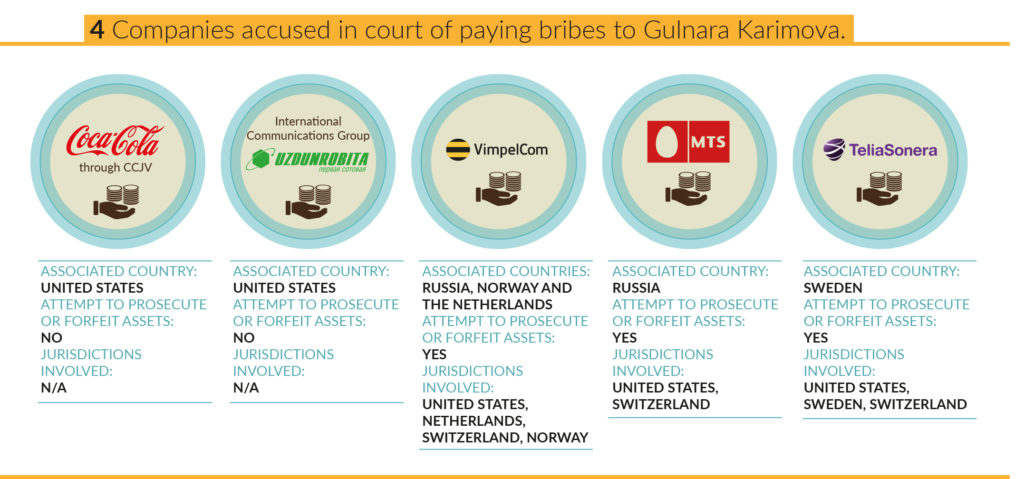

The International State Crime Initiative has been investigating the case of Gulnara Karimova over the past 18 months. She is the daughter of former Uzbek President, Islam Karimov, who passed away in September last year. Gulnara Karimova is accused by US authorities of having obtained over US$850 million from bribes paid by multinational telecommunications companies headquartered in Sweden, the Netherlands and Russia.

These proceeds of crime have been frozen, and are currently the subject of multiple forfeiture proceedings. In the US, the civil forfeiture action is yet to go to trial.

But civil society has been anticipating a positive outcome. And our efforts have been concentrated on confronting the difficult policy challenges that will emerge if the assets are successfully seized.

Chief among these challenges is the way in which the stolen asset return process is framed in law. The implicit presumption is that stolen assets should be returned to the state of origin. So the government is generally assumed to be the victim. And where non-state victims are considered, its through a tortious lens, where claimants must be able to demonstrate direct economic loss resulting from the illicit conduct in question.

So in the Uzbek case, civil society has played a really important role in thoughtfully considering whether this status quo should indeed be applied to the Karimova assets.

There are a number of spokes to this civil society effort, that I would like to point to.

First, research has been conducted into Karimova’s alleged illicit activities, in order to better understand whether she was in fact a lone operator who abused her position of power to defraud the state. Answering this question will help to determine whether the state of Uzbekistan should in policy be framed as a victim.

The research, conducted by myself, and colleagues at Ulster University and Queen Mary University, has concluded that the evidence indicates that Karimova in fact headed a multi-billion dollar business empire, which had both licit and illicit dimensions. This empire required an expansive administrative apparatus made up of advisers, managers, fixers, envoys and proxies. As a result, we concluded it is appropriate to label this group led by Karimova a state-organised syndicate.

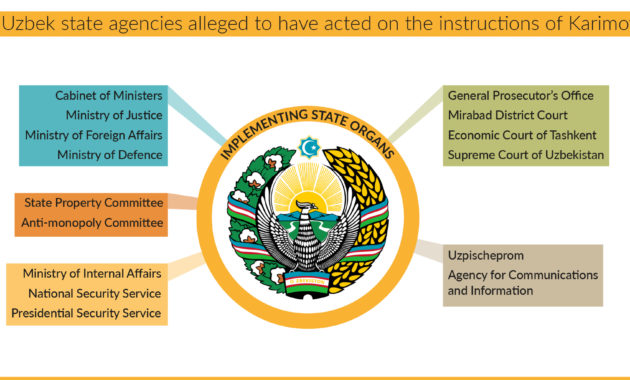

During our research, we uncovered evidence which suggests senior members of the Uzbek political and security apparatus played important roles in the syndicate’s activity. They were joined by experienced financial and professional service providers.

Through this expansive structure, which reaches into the deep state, the syndicate was able to successfully organise a range of profitable illicit enterprises.

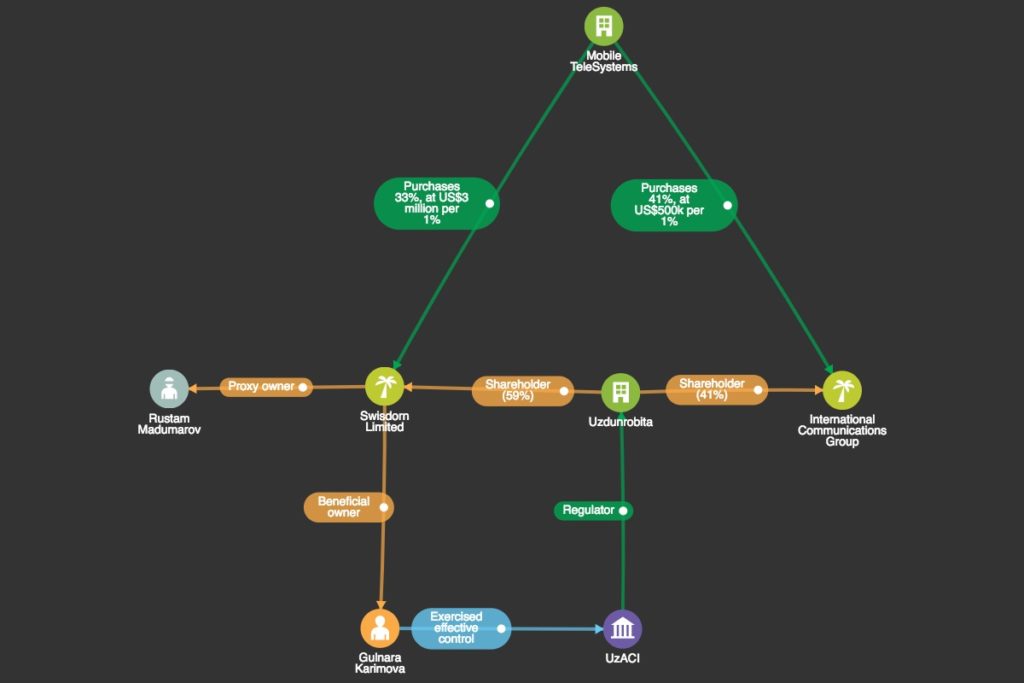

For instance, by exerting effective control over the industry regulator in the telecommunications sector the Karimova syndicate was able to act as a gatekeeper. In order to access the telecommunication market, aspiring companies needed to pay the syndicate an entry fee, and regular protection payments.

By exerting effective control over the courts, the syndicate was able to expropriate businesses, and destroy market rivals.

Through Karimova’s extensive political leverage, the syndicate could sell political concessions, such as currency conversion privileges.

I will use just one example which demonstrates how the syndicate is allaged to have operated in Uzbekistan through the state system.

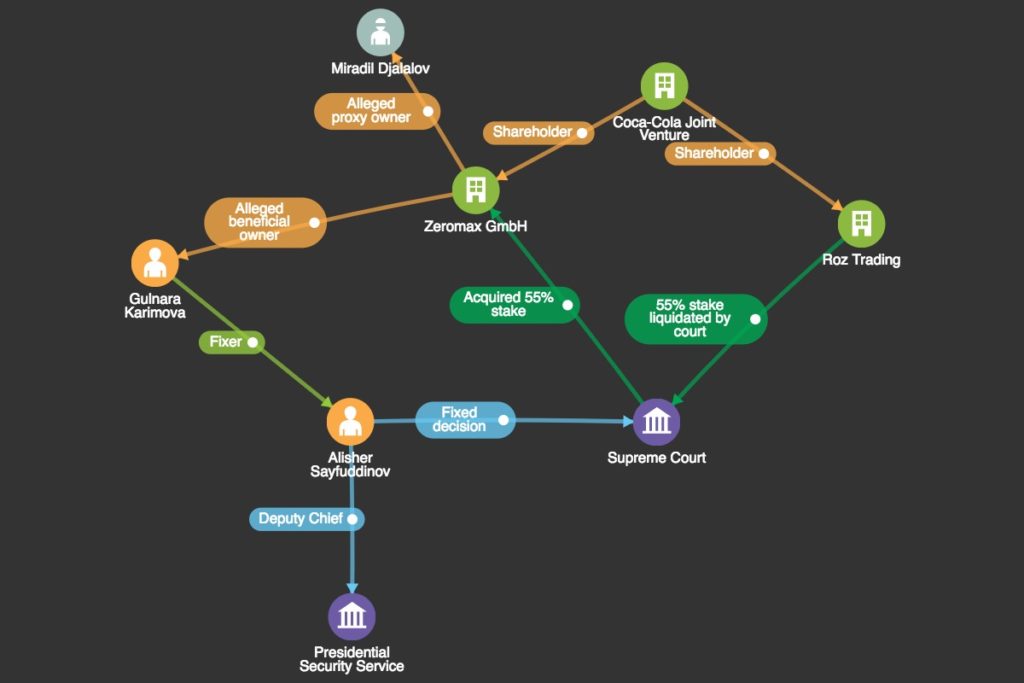

This example involves the Cayman Island company Roz Trading Limited, which enjoyed a 55% stake in Coca Cola Bottlers of Uzbekistan, a highly profitable joint venture. In 2001 both Roz Trading and Coca Cola’s premises were raided by the National Security Service, and senior managers were interrogated. This was one of many examples we came across where Karimova was accused of using the security services to arrest and terrorise business targets.

In the Coca-Cola case, the state enacted court proceedings, seizing Roz Trading’s stake in the joint venture, worth approx. US$150 million. According to Karimova’s former financial adviser: ‘Ms. Karimova … reviewed, edited, and approved these [court] decisions. Ms. Karimova often wrote substantial portions of the decisions herself to make sure that they contained the exact language and ordered the precise outcome she desired’.

So you can see here why we chose to label the activity state-organised. For instance, Karimova in this case appears to have employed the Deputy Chief of the Presidential Security Service to fix court decisions. And as a result, the syndicate was allegedly able to have Roz Trading’s 55% stake in the Coca-Cola joint venture in effect transferred to the Swiss company, Zeromax. A wide range of source indicate that Zeromax at the time was beneficially owned in part by Gulnara Karimova. A relationship that was allegedly concealed by a proxy shareholder, who is a close family friend of the Karimovs.

Similar evidence presented in prosecutions, civil claims and audits, suggest again that the Karimova syndicate asserted effective control over the telecommunications regulator which issued licenses and frequencies to companies wishing to provide consumers with mobile services. This enabled the syndicate to charge telecom companies an illicit access fee, which was concealed through sham sales contracts, share-swap agreements and consultancy arrangements.

Another key finding which emerged from the research worth noting, centered on the role played by transnational actors.

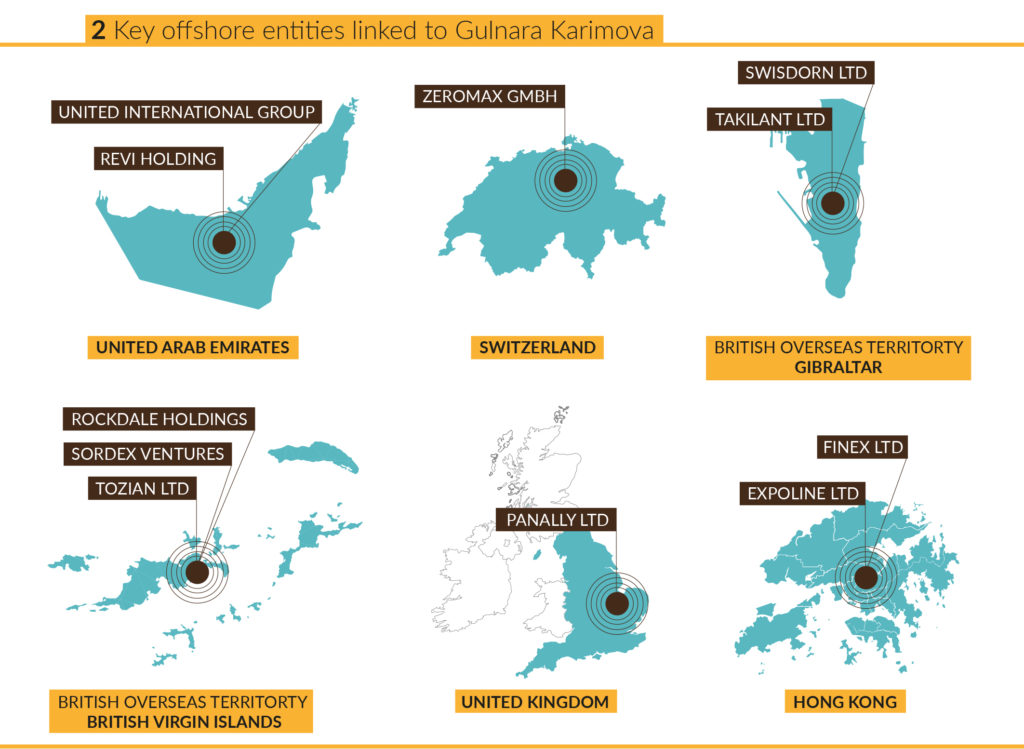

For example, formally speaking the protection racket which the Karimova syndicate oversaw in Uzbekistan’s telecommunications industry, was primarily operated from the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar. Other holding companies employed by the syndicate were incorporated in the British Virgin Islands, Switzerland and Hong Kong, jurisdictions which all score poorly in the Financial Transparency Index.

Because the syndicate was handling billions of dollars in foreign currency, which was held offshore, it of course also made extensive use of international banking services, to launder the proceeds of its activities. Arguably, the two most important players were the British Bank, Standard Chartered, and Swiss bank, Lombard Odier, both of whom have been prosecuted in the US for offences relating to money laundering and tax evasion.

Because the syndicate was handling billions of dollars in foreign currency, which was held offshore, it of course also made extensive use of international banking services, to launder the proceeds of its activities. Arguably, the two most important players were the British Bank, Standard Chartered, and Swiss bank, Lombard Odier, both of whom have been prosecuted in the US for offences relating to money laundering and tax evasion.

So we concluded that Karimova’s activities were both state-organised and transnational in character.

Accordingly, it would be highly problematic if the stolen assets were returned to the government of Uzbekistan. It would in effect mean that stolen assets were given to the organisational perpetrator of the theft. Furthermore, it would also pose a substantial risk that the returned assets would be re-stolen by criminal syndicates currently operating through the Uzbek state system.

So, if the state is not the victim, then who is. This is a very complicated question. Most immediately we can point to individuals, executives and businesses who have been persecuted by the Karimova syndicate, leading to loss of property and gross human rights abuses.

However, it also apparent that the type of illicit activities perpetrated by the syndicate are systemic in Uzbekistan. In effect, while the Soviet Union as an ideological entity has been liquidated its teeth and power are now employed in by elite cabals in Uzbekistan to maintain their position of power, undemocratically, and to illicitly generate wealth through protections rackets, extortion rackets, expropriation and kidnap & ransom.

The SNB, formerly the KGB, is a central hub for coordinating these illicit endeavors. So we might also argue that those targeted by the security services, through illegal raids, torture, detention and imprisonment, are also victims of this system of state-organsied crime, and should have a claim on any proceeds seized from these activities.

Finally, the noxious way in which authoritarian politics and racketeering have become entwined in Uzbekistan has created a situation where citizens are unable to participate in any meaningful sense in the political, and economic life of the nation. And they too need to be seen as victims of this system of corruption, which the Karimova syndicate exploited to make considerable profits.

Needless to say then, it doesn’t make much sense in this context to talk about returning assets to the Uzbek state, or for that matter differentiating individual victims on the basis of direct loss. We need to build alternative principles, policies and return structures, that can deal with illicit activity that is state-organised in nature, and which produces social harm on a mass scale.

So those of us in civil society dealing with the Karimova case have set up a working group, which includes involvement from Uzbek exiles and NGOs with expertise in these matters including Transparency International, Public Eye, SHERPA, Open Society, and the Civil Forum for Asset Recovery.

First of all we are briefing justice officials and policy makers involved in the asset return process on the delicate challenges posed by the Uzbek case, given the data I have just outlined. Also, we are posing potential solutions.

In this respect, the working group is arguing that the stolen assets could be returned through a trust arrangement, similar in style to the BOTA foundation which was used to return stolen assets to Kazakhstan. The Trust, we argue, could provide a flexible space for handling the stolen assets. And perhaps most critically in this respect it could be used to engage victims directly in the asset return process, so their representatives can have a voice in both the return mechanisms and the desired outcomes.

Also I think it is important to note that the Trust could have a specific mandate to use the returned funds for the broad purpose of restituting victims, and contributing towards non-reoccurrence. In effect the Trust becomes a created democratic space where victims and civil society can joint together in a bid to use the assets for socially useful ends.

So at the moment we have produced policy papers and research reports, setting out these positions in detail. The working group is now promoting these materials through workshops and one to one meetings, in the US, Netherlands, Switzerland, Ireland and Brussels in particular.

I guess, in effect it might be said we are trying to build a sustainable policy approach for dealing with stolen assets, when they emerge from corruption that is state organised in character, and when this corrupt activity, effects a diverse range of groups, making any tortious approach to victimhood redundant.

And of course we would be delighted to hear from anyone who might be able to assist us in making this aspiration a reality. So here are my contact details!

Thank you very much.