Art and the Wounds of the Argentine Dirty War: Deepening Resistance by Documenting Horror and Preserving Memory

Art and the Wounds of the Argentine Dirty War: Deepening Resistance by Documenting Horror and Preserving Memory.[1]

By declaring that it would be barbaric to write poetry after Auschwitz,[2] German philosopher Theodor W. Adorno gave rise to a fundamental question: ‘Is inhumanity unrepresentable?’ According to Horacio González, this ‘two–fold negation’ is inconvenient for the domain of art since, ‘it would entail evicting art from the very site where its most radical test is found, […] that which consists of creating a meaning for damaged humankind.’[3]

Although Adorno’s famous statement is usually taken to mean that, if we are to talk about Auschwitz, we should use its own language[4]—rather than a more radical claim that there would be no ‘art value’ in poetry about the Holocaust—it seems that the author himself was later forced to recant: ‘Perennial suffering has as much right to expression as the tortured have to scream; hence it may have been wrong to say that after Auschwitz you could no longer write poems.’[5]

In the case of Argentina—a state that is still dealing with the legacy of the terror inflicted during its ‘Dirty War’—it would seem that, ‘art as a social practice adds its efforts to the (always insufficient) task of reconstructing memory and the cultural fabric that was torn apart by the last military dictatorship.’[6] In this context, ‘memory’ is a term that encompasses claims for truth, justice and accountability. On the premise that, ‘we should be open, in principle, to different possibilities of representing the real and memories of it,’[7] it is worth exploring whether art has the capacity to actively participate in the process of constructing and reconstructing the memories recovered in Argentina’s post terror democracy.

The monument to the victims of state terrorism and the sculptures installed in the Parque de la Memoria—such as Claudia Fontes’ Reconstrucción del Retrato de Pablo Míguez, Nicolás Guagnini’s 30,000, and Marie Orensanz’s Pensar es un Hecho Revolucionario; the Nosotros No Sabiamos collages, by León Ferrari; the Buena Memoria, by Marcelo Brodsky; Gustavo Germano’s set of photographs, Ausencias; and the Manos Anónimas series, by Carlos Alonso… are just a few examples of the way in which artistic work engages in the construction of the collective memory.[8] Moreover, they show how art can emerge as a critical form of resistance.

The violent tactics employed by the Argentine military government between 1976 and 1983—kidnappings, torture, public executions, show trials, extra-judicial assassinations, or arbitrary arrests, to cite a few—were extremely well suited to instilling significant and effective terror: that is, fear that subjectively and symbolically affects a broad population, beyond the particular persons targeted. One of the most efficient methods adopted in Argentina to achieve the desired combination of publicity and concealment was the use of disappearances. According to the International Criminal Court Statute, ‘enforced disappearance’ refers to acts of arrest, detention or abduction conducted directly or indirectly by a state, which are ‘followed by a refusal to acknowledge that deprivation of freedom or to give information about the fate or whereabouts’ of the victim.[9]

The following photographs encourage us to analyse the strategies employed by artists to represent the one that was once rendered invisible by the state. Although it is said that, ‘[e]very photograph is a certificate of presence,’[10] one might wonder whether the images below show the presence of an absence or the absence of a presence. Be that as it may, the disappeared seem to settle down in our memories. Critics may challenge the art as politics but as León Ferrari attests: ‘It is possible that someone will show me that this is not art; I would have no problem, I wouldn’t change path, I would only limit myself to change the name of what I do: I would cross out art and call it politics, corrosive criticism, whatever.’[11] Or maybe… resistance?

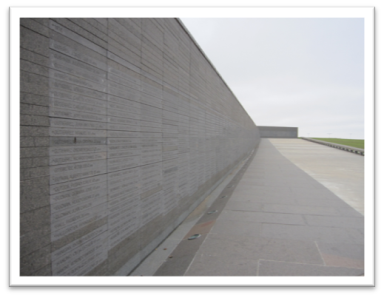

The ‘Park of Memory / Monument to the Victims of State Terrorism’—Parque de la Memoria / Monumento a las Víctimas del Terrorismo de Estado (1997-2007)—is a public institution situated in the city of Buenos Aires, on the shores of the Río de la Plata. This site for memory is made of a monument bearing the names of the ‘disappeared’ that runs toward the river, into whose waters many of the victims were hurled.

The ‘Reconstruction of the Portrait of Pablo Míguez’—Reconstrucción del Retrato de Pablo Míguez (1999-2010)—is a sculpture installed in the Parque de la Memoria. Claudia Fontes offers the figure of a young boy—representing Pablo Míguez, kidnapped when he was14 years old—standing on the water, looking out at the horizon and having its back to the park. The piece is located approximately 70 meters from the coast, on a floating platform anchored in the river in such a way that it appears and disappears according to the movements of the water, reinforcing the symbol of disappearance.

Nicolás Guagnini’s installation—titled ‘30,000’ (1999-2009)—consists of 25 white rectangular columns arranged vertically to form a cube on which a face is painted in black. At once, the image is not neat but, as the viewer moves around the cube, he or she comes across an ideal viewing point that permits the face of Guagnini’s father to appear against the background view of the river in the Parque de la Memoria. This autobiographical piece also highlights the condition of the disappeared—that is, being absent and present at the same time.

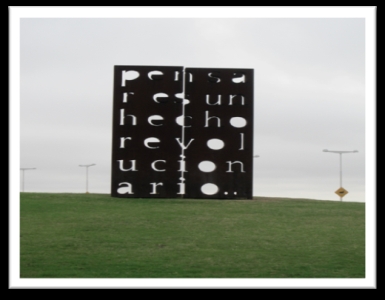

Marie Orensanz’ work (1999-2010) consists of two tall steel blocks, slightly separated from one another, perforated by a text so that the viewer who wishes to compose the fragmented phrase must read the void. The aesthetic underlines the idea of brokenness whereas the meaning of the words—Pensar es un Hecho Revolucionario (‘Thinking is a Revolutionary Act’)—reminds us that, at the time of the Dirty War, acts as trivial as carrying a book could awaken suspicion and result in a person being labelled as a subversive.

Leon Ferrari’s Nosotros No Sabiamos (‘We Didn’t Know’) is a collection of newspaper notes from 1976 to 1983, reporting on disappearances and reappearances of mutilated bodies in Argentina during the dictatorship. In the years following the Dirty War, ‘we didn’t know’ was a phrase repeated by a large section of the population which refused to acknowledge state terrorism. This expression evokes the negligent and complicit attitude of a large part of civil society. By highlighting a reality that everybody could perceive, Ferrari demonstrates that ignorance was impossible: people knew, people suspected, people feared.

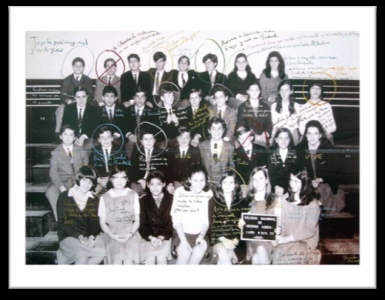

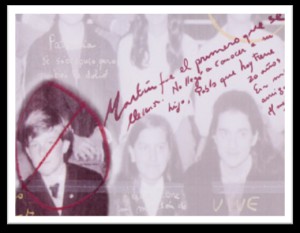

In 1997, Marcelo Brodsky created Buena Memoria (‘Good Memory’), a tribute to his murdered school friends and his missing brother, Fernando. His project’s starting point—and best known work—is an enhanced photograph of the 1967 graduating class of the Colegio National de Buenos Aires (‘National High School of Buenos Aires’), covered with inscriptions and comments on the classmates. Brodsky used personal and literary quotes around this image to reconstruct the life stories of his friends. Each time that Brodsky puts a cross on a classmate’s face, he refers to one of the 98 students of the Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires who were murdered by the state during the dictatorship. For example, the enlargement of Brodsky’s photo contains the message, ‘Martín was the first one to be taken away. He didn’t get to know his son, Pablo who is twenty years old now. He was my friend, the best.’

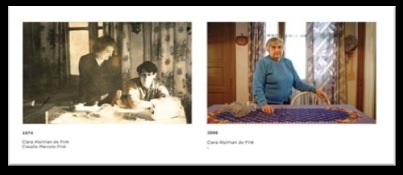

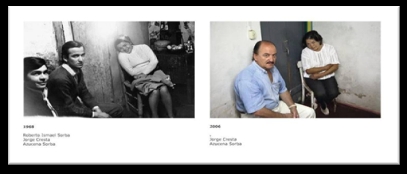

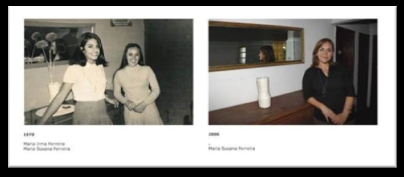

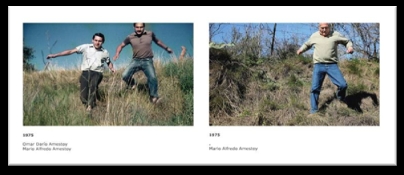

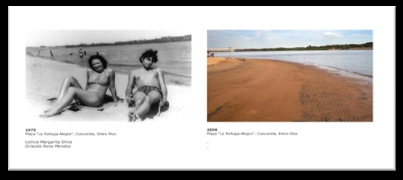

The next set of photographs, the work of Gustavo Germano, Ausencias (‘Absences’), consist of sets of two photographs. Each photographic pair offers two separate images; the first one is usually an old family photo and the second one is a more recent shot—taken between 1989 and 1999—with an attempt to capture the same people with a similar background. However, as it can be seen, the tactic of forced disappearance employed by the military government during the Dirty War renders this project hard to realise for the photographer; in Germano’s work, a person is always missing when all are not absent.

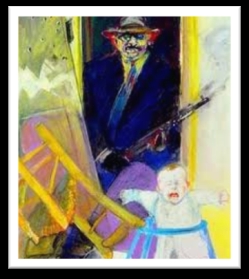

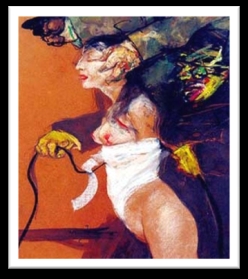

Carlos Alonso’s works, entitled Manos Anónimas (‘Anonymous Hands’), throws another light on the Argentine recent history signed by arrests, tortures, forced disappearances and illegal appropriations of children. The series was acquired in 2007 by the Government of the Province of Córdoba for its public exhibition in the Museo de Bellas Artes Evita, Palacio Ferreya. The first painting on the left hand-side, Manos Anónimas III (1984), shows a woman being physically but also mentally tortured—besides the whip, the bandage around her belly suggests that she just gave birth but her baby was taken away from her. The second one, Manos Anónimas V (1984), highlights another Argentine state crime—the only one that was not covered by the two amnesty laws, the 1986 Ley de Punto Final and the 1987 Ley de Obediencia Debida—that is, the illegal appropriation of children.

[1] Many thanks to Marisa Bellani, graduate student in History and Theory of Photography from the Sotheby’s Institute of Art, who introduced me to the work of Marcelo Brodsky and the interplay between presence and absence in photography.

[2] Adorno, T. W. [1955] (1986) Prismes: Critiques de la Culture et de la Société, Translated in French by G. & R. Rochlitz, Paris: Payot, p. 23.

[3] González, H. (2007) ‘La Materia Iconoclasta de la Memoria’, in S. Lorenzano and R. Buchenhorst (eds) Políticas de la Memoria: Tensiones en la Palabra y la Imagen, Buenos Aires: Gorla, p. 34.

[4] Carlevaro, V. S. (2007) ‘A Propósito de la Posibilidad (o Imposibilidad) de un Acercamiento Estético al Horror’, XI Jornadas Nacionales de Investigadores en Comunicación, Mendoza: UNCUYO, p. 21.

[5] Cited by Chéroux, C. (2007) ‘Por qué Sería Falso Afirmar que Después de Auschwitz no Es Posible Escribir Poemas?’, in S. Lorenzano and R. Buchenhorst (eds) Políticas de la Memoria: Tensiones en la Palabra y la Imagen, Buenos Aires: Gorla, pp. 219–231.

[6] Battiti, F. (2010) ‘Art in the Face of the Paradox of Representation’, Catálogo Institucional Parque de la Memoria, p. 70.

[7] Huyssen, H. (2002) En Busca del Futuro Perdido: Cultura y Memoria en Tiempos de Globalización, México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, p. 26.

[8] Foucault, M. [1969] (2002) The Archaeology of Knowledge, London: Routledge, pp. 248-251.

[9] Art. 7(2)(i).

[10] Barthes, R. (1981) Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, Translated in English by R. Howard, New York: Hill and Wang, p. 87.

[11] Ferrari, L. (7 October 1965) ‘La Respuesta del Artista’, Propósitos: Buenos Aires.