The Saville Report: A Personal Reflection

This was a Berlin Wall moment. With the thousands of others in Guildhall Square, Derry on June 15th 2010, I was glued to a giant television screen to hear David Cameron in the House of Commons comment on the Saville Report twelve years in the making and running to 5000 pages into the deaths of 14 civil rights marchers in the city on January 30th 1972 at the hands of British paratroopers. Saville concluded what every right-thinking person has known since the event, that the dead were all innocent. Cameron announced that Saville had pointed the finger of blame at the Parachute Regiment and their commanding officer. He acknowledged that the deaths were unjustified and unjustifiable and said that no democratic state had anything to gain from failing to tell the truth. He apologised with what seemed to be genuine sincerity on behalf of his government and country and was applauded loudly and warmly by the largely nationalist and republican crowd. This was a moment that in the darkest days no one in the Square, least of all the relatives of the dead, had ever expected to experience.

This was a Berlin Wall moment. With the thousands of others in Guildhall Square, Derry on June 15th 2010, I was glued to a giant television screen to hear David Cameron in the House of Commons comment on the Saville Report twelve years in the making and running to 5000 pages into the deaths of 14 civil rights marchers in the city on January 30th 1972 at the hands of British paratroopers. Saville concluded what every right-thinking person has known since the event, that the dead were all innocent. Cameron announced that Saville had pointed the finger of blame at the Parachute Regiment and their commanding officer. He acknowledged that the deaths were unjustified and unjustifiable and said that no democratic state had anything to gain from failing to tell the truth. He apologised with what seemed to be genuine sincerity on behalf of his government and country and was applauded loudly and warmly by the largely nationalist and republican crowd. This was a moment that in the darkest days no one in the Square, least of all the relatives of the dead, had ever expected to experience.

The significance of the event cannot be underestimated. Civil rights died on the streets of Derry that day and here, 38 years later, was the discourse of human rights, not from the mouth of an international humanitarian organisation but from a British Tory prime minister. Words are easy, someone said to me afterwards, but I dont agree. Cameron surely knew that his words will not have gone over well in the darkest recesses of the British secret state. Besides, these are words that could come back to haunt the state when the British army next commits an atrocity, whether in Afghanistan or in some war yet to come.

At the risk of being churlish, however, despite the novelty, there were many ways in which a tired old script was rolled out again, one that we in the North of Ireland know well. There was no premeditated killing; there was no conspiracy; a commanding officer countermanded an order by sending in the Paras; a group of soldiers bad apples lost their composure and killed indiscriminately; the British army remains the most professional, humane and respected on the planet. This is our version of Stan Cohens states of denial. Lets unravel some of that script.

First, the issue of state killings. The British army and the local police force, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) accounted for just over 10 per cent of all the deaths in the Northern Ireland conflict, 357. The British army was responsible for 82 per cent of those deaths. 45 per cent of state killings occurred in the years 1971 to 1973, with Bloody Sunday right in the middle of that. In the early years of the conflict, the state was highly active in killing citizens. Ten of the 16 deaths which occurred in 1969 were due to state forces, and state forces killed 62 people before Bloody Sunday happened. In none of these cases was there a single prosecution of any soldier or police officer. This was the general atmosphere of impunity in the lead-up to Bloody Sunday.

No group seemed to be more protected than the Parachute Regiment. Five months before Bloody Sunday they had taken over the nationalist district of Ballymurphy in West Belfast for three days as internment without trial was introduced. While there, they killed eleven people, including a priest, and a woman, dressed in a dress in broad daylight as she went to the aid of a teenager who had been shot. Just over one week before Bloody Sunday, they had been sent to police a civil rights march on Magilligan Strand, a long beach near one of the internment camps. They used excessive, but not on that occasion lethal force to disperse the marchers.

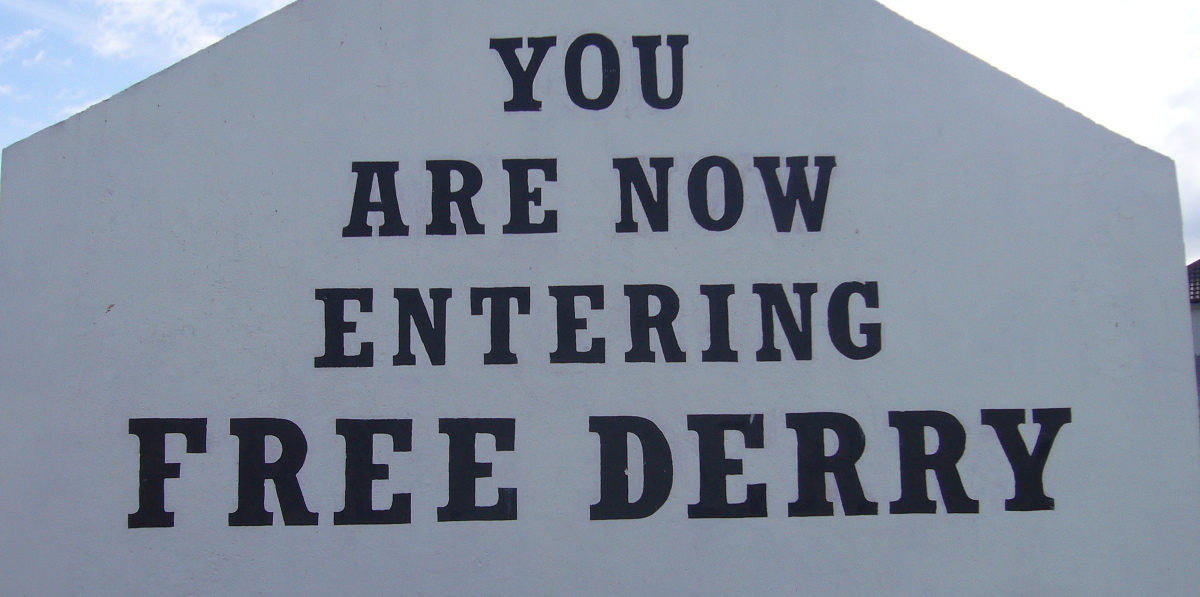

And then they were sent to Derry. Since summer 1969 most of the nationalist working class parts of Derry, the Creggan and Bogside, had been a no-go area for state forces. Barricades were erected and guarded, often by armed IRA personnel, and a gable wall carried in large letters the message: You are now entering Free Derry. Of course, that is precisely what state forces were not doing and which some, especially in the upper reaches of the British army, were intent on doing. Free Derry was a springboard for weekly running battles between nationalist youths and British soldiers. So, when the Major General Robert Ford, Commander of Land Forces in Northern Ireland, visited the city on January 7th 1972, he came away determined to teach the hooligans of Derry a lesson. In a memo he produced at the time he stated: I am coming to the conclusion that the minimum force necessary to achieve a restoration of law and order is to shoot selected ring leaders amongst the DYH [Derry Young Hooligans his title, not theirs] after clear warnings have been issued. Three weeks later, and without warning, the Paras killed 14 males, half of whom were aged 17.

And then they were sent to Derry. Since summer 1969 most of the nationalist working class parts of Derry, the Creggan and Bogside, had been a no-go area for state forces. Barricades were erected and guarded, often by armed IRA personnel, and a gable wall carried in large letters the message: You are now entering Free Derry. Of course, that is precisely what state forces were not doing and which some, especially in the upper reaches of the British army, were intent on doing. Free Derry was a springboard for weekly running battles between nationalist youths and British soldiers. So, when the Major General Robert Ford, Commander of Land Forces in Northern Ireland, visited the city on January 7th 1972, he came away determined to teach the hooligans of Derry a lesson. In a memo he produced at the time he stated: I am coming to the conclusion that the minimum force necessary to achieve a restoration of law and order is to shoot selected ring leaders amongst the DYH [Derry Young Hooligans his title, not theirs] after clear warnings have been issued. Three weeks later, and without warning, the Paras killed 14 males, half of whom were aged 17.

If that is not premeditation to murder, it comes remarkably close.

Then take the issue of conspiracy. After the event the British establishment closed ranks. Army chiefs issued statements to the effect that all the dead were gunmen, nailbombers or apprentice nailbombers. The British government and politicians agreed and slurred the reputation of the dead. An inquiry was set up under former Lord Chief Justice Widgery which worked hastily and superficially, concluding that while some soldiers actions had been reckless, the killings had resulted from the armys reaction to being under attack. It was likely, said Widgery, that as many rounds were fired at the troops as were fired by them; given that, only their professionalism ensured that none of them was in fact injured, even slightly.

Conspiracy to cover up murder is as real and as culpable as conspiracy to murder.

In the face of that conspiracy, Savilles conclusions are remarkable. The immediate responsibility for the deaths and injuries on Bloody Sunday lies with those members of Support Company whose unjustifiable firing was the cause of those deaths and injuries… none of the casualties was posing a threat of causing death or serious injury, or indeed was doing anything else that could on any view justify their shooting.

So, lets accept the Saville Report and Camerons apology for what they are: an acknowledgement of innocence, an almost unprecedented finding of guilt. This is probably as good as it ever gets. This may not be justice, but it is something approximating truth. And even truth and acknowledgement can be a form of justice whether or not prosecutions ever follow. At the same time, lets also see Savilles shortcomings: there was a regime of impunity and a determination to teach the people of the Bogside a lesson which, if not direct premeditation gives the green light to soldiers to kill; and not just any soldiers, but the elite, the Paras; and there was a conspiracy after the event to libel the dead, lie and cover up for murder.

Six months after Bloody Sunday British army chiefs had their way; Operation Motorman smashed Free Derry; there were no more no-go areas. By that time the IRA had more recruits than they had room for and the war was on in earnest. It was three decades before peace became firmly rooted in the North again. And during that time the relatives of the Bloody Sunday dead marched, campaigned and organised, often in the face of official dismissal or worse, suggestions that they were, if not terrorists themselves, at least playing into the hands of terrorists. June 15th 2010 was their vindication; they were not mad, they were not bad. The people of Derry always knew that, but now they have the seal of approval from none other than a British Lord and a British Tory prime minister.