The Outing of Torturers in Argentina: Civil Society and the Ongoing Fight Against Impunity.

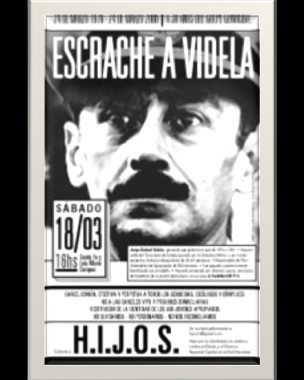

Buenos Aires, Argentina, 18 March 2006, 4 pm. People were given maps and fliers: ‘Escrache a Videla’, organised by the members of a certain organisation called ‘H.I.J.O.S.’. Dozens of mostly young people had begun to converge on the designated street corner: ‘Avenida Santa Fe y Luis María Campos’. They had prepared their signs, placards, photographs, and banners. The air was tense with anticipation. The noise of drums and whistles was persitent. Suddenly the activist marchers broke out in unison: ‘Attention, attentition, attention neighbours! There is a torturer living next door!’[1]

On 30 October 1983, the dictatorship came to an end in Argentina and democratic elections were held, marking the return of civilian rule. Shortly after, members of the military began to be brought to trial and sentenced to imprisonment. But the need for accountability was frustrated when President Raúl Alfonsín’s Government—under threat of a new military coup d’état—enacted the 1986 Ley de Punto Final[2] and the 1987 Ley de Obediencia Debida,[3] both of which afforded immunity from prosecution to members of the former regime. Moreover, just two years later, President Carlos Menem, who felt that the support of the military would benefit his party as well as the country, granted a pardon to already convicted or still indicted members of the junta.

As a result, people had to share societal spaces—such as streets, restaurants, bars, hotels, official ceremonies, and even significant public office[4]—with hundreds of represores.[5] This meant that face to face encounters between victims and their former torturers were rendered possible.[6] This kind of ‘daily crime’[7] allowed an unhealthy tolerance for criminality to develop—what Kaiser calls the ‘normalisation of living with represores’[8]—which, in turn, led to what has been described as a ‘social trauma.’[9] For example, although amnesty laws did not cover the stealing of babies born in captivity,[10] one of the most disturbing forms of this ‘normalisation’ was that some Argentines were willing to allow the represores to keep the children they had kidnapped after torturing and disappearing their biological parents.[11] As Kaiser explains: ‘These attitudes reveal a distortion of public values, a legacy of terror left behind by the dictatorship.’[12]

But Argentine civil society refused to turn its back on the search for truth and justice. Of course, there was the famous organisation of the Madres y Abuelas de la Plaza de Mayo who continued, and still continue, to seek clarification of the fate and whereabouts of the disappeared. But they were no longer alone. As visually emphasised at a march in June 1996 commemorating 1,000 Thursdays of their weekly marches, the mothers and grandmothers were followed by a contingent of H.I.J.O.S. (Hijos e Hijas por la Identidad y la Justicia contra el Olvido y el Silencio),[13] an organisation of the children of the people who disappeared or were forced into exile during the dictatorship. At that event, the daughters and sons were walking well behind their elders, suggesting that the ‘disappeared’ were marching in-between and, thus, allowing the missing generation to be ‘metaphorically and powerfully present.’[14]H.I.J.O.S.—like the Madres y Abuelas—claim ‘institutional justice, not private vengeance.’[15] More particularly, the children of the disappeared challenge the artificial and premature reconciliation resulting from the vagaries of amnesties: they want Juicio y Castigo (‘Justice and Punishment’). As such, they have developed an effective communication strategy, namely escraches[16]—from the verb escrachar, an Argentine slang term meaning roughly ‘to expose’ or ‘uncover’.[17]

Through the escraches movement, H.I.J.O.S. have disturbed the peaceful impunity enjoyed by former military officers who benefited from the amnesty laws of the 1980s. Escraches publicly expose torturers and killers to neighbours, colleagues, passers-by and the community. Once their protective shield of anonymity is torn away, the represores become trapped in ‘metaphorical jails’ throughout Argentina.[18] The targets of escraches range from little-known physicians who assisted in torture sessions to General Videla, the military leader of the Junta between 1976 and 1981.[19] The motto of H.I.J.O.S. is: Si no hay Justicia, hay Escraches—‘If there is no Justice, there is Outing.’[20] This is particularly emphasised in the following testimony of a member of H.I.J.O.S.:

‘‘We, the children of the disappeared, are not guilty for what is happening in the Argentine society […] What we can do is to preserve the history of our parents […] We must seek after the moral sentencing of the murderers. And bring off the social punishment. So that the country will be a prison for them […]’’[21]

Usually, escraches are loud, festive but serious, provocative and mobile demonstrations involving 300 to 500 people.[22] The marchers invade the surroundings of a clandestine torture center or the neighbourhood of the person being ‘escrachado’ (‘outed’) and inform the community about what this place used to be or who their neighbour really is, handing out fliers with the perpetrator’s photograph, name, address, current occupation, place of work, and information about the human rights violations in which he is implicated. There are also vans with loudspeakers, churning out music and running commentary such as, ‘Neighbours, listen up! Did you know that you live next to a concentration camp/an assassin?’ or ‘Just like the Nazis it will happen to you, wherever you go we will go after you.’[23]

The demonstrations end outside the escrachado’s homes where eggs are tossed at his door, red paint is thrown at his façade, slogans are written on the walls and yellow footprints are painted on the sidewalks.[24] The doorstep can be washed and the stains on the house and pavement can be erased, but the ‘social marks’ now worn by the escrachado will remain.[25] Typically, the effects are felt by the represor the following days: ‘That’s when the baker won’t sell him bread, the taxi won’t pick him up, the newspaper won’t come to his house.’[26]

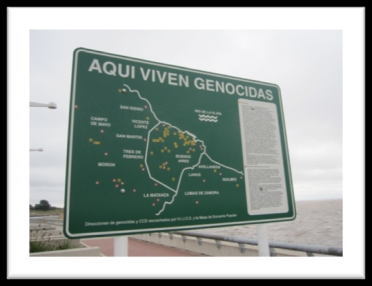

This sign is part of the Grupo de Arte Callejero’s larger project displayed at the ‘Parque de la Memoria’—a public institution situated in the city of Buenos Aires, on the shores of the Río de la Plata—named ‘Carteles de la Memoria’ (1999-2010), a urban intervention made of 53 road signs, measuring 2.6 m each.

Clearly, escraches are an effective instrument of the fight against impunity. But more than that, they are part of Argentina’s current battle over memory. Indeed, for the children of the disappeared who grew up without their parents, memory is also a political project[30]: ‘[T]ruth and accountability are debated, and different historical explanations compete for hegemony. The escraches act as alternative history textbooks, overcoming the legacy of silence and fear that has resulted in a fragmented, decontextualised knowledge of the dictatorship era.’[31] As Nora has argued, ‘It is up to each generation to rewrite its generational history.’[32] In the political process of the reconstruction of a common history after the return of democracy in Argentina,[33] the ‘children of the disappeared generation’ started transmitting its memory through a process that resembles ‘contagion’:[34]

‘‘Traumatic experience may be transmittable, but it is inseparable from the subject who suffers it.’’[35]

But, H.I.J.O.S.’s communication strategy doesn’t stop there: By revealing the human rights violators’ identity and whereabouts, escraches force people to leave their society’s bystander role.[36] The fight for truth and accountability is not a task reserved only for the direct victims of the repression and their families, it is a responsibility that is incumbent on all civil society. That fight has not been won yet. In the meantime, the children of the disappeared vows to maintain the escraches until justice has been served and memory preserved.