The city as a space of power and exclusion

Dr Kristian Lasslett, Senior Lecturer in Criminology

3 May 2016

Introduction

Today The Opposition premieres at the coveted Hot Docs festival, after parrying systematic efforts to silence the film in the Australian courts. It documents arguably the most controversial real-estate venture in the history of Papua New Guinea (PNG), which centres on a 14 hectare tract of land in the nation’s capital known as Paga Hill.

The real-estate venture precipitated a five year struggle to save Paga Hill from the developer’s knife, which left in its wake mass demolitions, serious human rights abuses and allegations of transnational corruption.

However, this film is not only about Paga Hill or indeed PNG. It is a timely warning siren that challenges the audience to peer behind the cosmopolitan glamour of gentrification, and witness the creeping form of social cleansing hidden beneath.

It also takes on with unflinching courage the global nexus of political, financial and property interests standing behind real-estate speculation that has turned cities into casinos – playgrounds for the rich and powerful, while the poor serve the drinks and deal the cards.

The trailer can be viewed here:

Paga Hill is not only an iconic PNG landmark, it is emblematic of a global process that is forging urban dystopias. From London to Mumbai, cities are becomes spaces of exclusion, rather than inclusion; places that transforms not to the beat of human need, but to power in its rawest forms.

The Opposition shows with intimacy and penetrating clarity how power and the city function. By taking a forensic lens to the case of Paga Hill, we can therefore begin to understand the hidden dynamics at the heart of what Neil Brenner calls planetary urbanisation.

The Paga Hill Estate – A vision for a ‘progressive’ future

Once designated a national park, the majestic surrounds of Paga Hill have been eyed by numerous real-estate developers over the years. However, it is the Paga Hill Development Company (PHDC) which succeeded in clearing the land of its residents and national park status.

This paved the way for a development that will evidently include luxury hotels, 800+ residential apartments, sporting facilities, marina precinct, and multi-use commercial precinct.

PHDC boasts, ‘with tourists and visitors staying at the Hilton Hotel, residents of the site, together with city visitors enjoying the waterfront retail, restaurants and marina complex, the area will be a buzzing melting pot, creating a new image for a progressive Papua New Guinea’ (Hilton Hotels strongly denies any involvement in the project).

Even among the rubble produced by a brutal demolition exercise in 2012, the site’s development value is readily apparent.

Of course it is always important to ask, who in particular will benefit from the proposed real-estate venture? Rarely are such projects universally beneficial.

We at least know one core clientele. It was recently announced that the estate ‘will be the venue for the Leaders’ meetings at the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation summit in Port Moresby’ slated to take place in 2018.

This is one of the most important multilateral forums in the Asia-Pacific region. If this announcement is true – unlike the partnership with Hilton Hotels – this gives the venture a special strategic importance for the summit’s principal sponsors the PNG and Australian governments.

Although the construction timeframe looks tight, PHDC has announced that the Shenzhen based, Zhongtai company, will collaborate in the development, with Chinese government backing.

The project also evidently has the support of the National Capital District Commission and PNG’s national government. According to PHDC’s website the ‘PNG Government will provide the support through relaxation of import duties and taxes’.

However, over its twenty year lifespan what is perhaps most striking about the Paga Hill Estate is the project’s ability to weather controversy. In 2007 the Public Accounts Committee accused PHDC of acquiring the land through ‘corrupt dealings’.

Five years later the project hit the headlines again after residents faced a brutal demolition exercise, executed by the Royal PNG Constabulary, allegedly at the behest of the company. This event became iconic when the opposition leader, Dame Carol Kidu, was frogmarched from the scene by police officers who had used live ammunition on residents. She argued PHDC was not an appropriate company to be entrusted with Paga Hill (Kidu later retracted her statement, and entered into a consultancy contract with PHDC).

In October 2012 matters got worse when it was reveal that PHDC’s CEO, Gudmundur Fridriksson, has managed or owned businesses censured in investigations conducted by the Public Accounts Committee, the Auditor General’s Office and the Commission of Inquiry into the Department of Finance – seven in total.

The details were covered extensively by the Australian media, although sadly little of the controversy made its way into PNG’s muzzled press. That said, PNG citizens have created a vibrant social media alternative, which became a vital hub for circulating information on Paga Hill.

A month after this expose Fridriksson took leave from an Australian government funded think-tank where he was CEO, evidently to pursue business interests in PNG. His presence has now been wiped entirely from their website.

The wife of prominent Australian indigenous lawyer Noel Pearson – the latter is a key figure behind the think-tank – then disinvested of her shares in PHDC during January 2013.

Despite the turbulence, Papua New Guinea’s O’Neill Government has time and time again rallied behind the venture. Ministers have issued supportive press statements, the government real-estate firm NHEL agreed to partner in the project on a 50/50 basis, and the development is now receiving generous tax breaks.

This is nothing new, from the project’s very inception in 1996 the executives pushing this luxury estate have proven adept at garnering support from some of PNG’s most powerful political forces.

A rejected planning application and Michael Nali MP

The first major challenge to getting the project off the ground was rezoning the land at Paga Hill and obtaining an Urban Development Lease. Back then it was the Paga Hill Land Holding Company (PHLHC) – a precursor to the Paga Hill Development Company – which led the way.

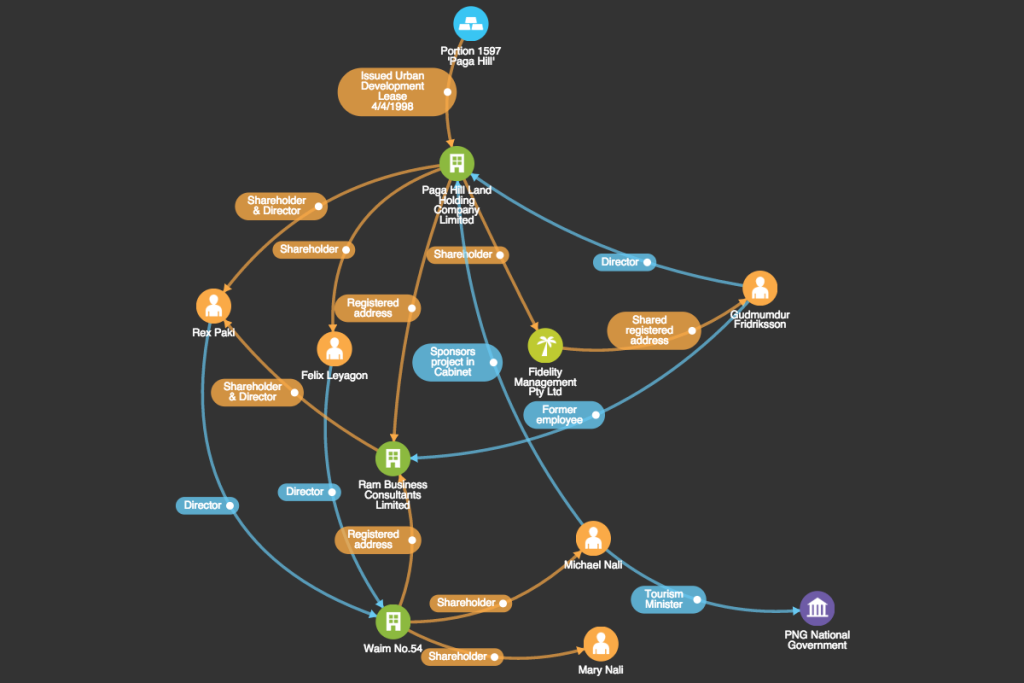

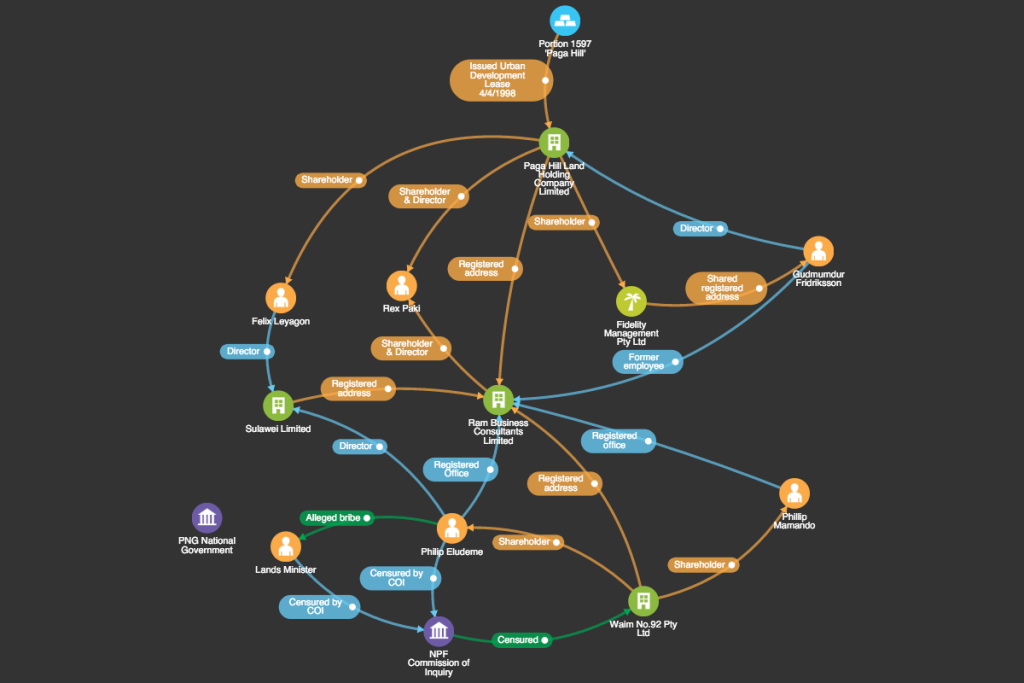

According to Investment Promotion Authority records – Papua New Guinea’s corporate registry – its shareholders included Rex Paki, Felix Leyagon, and the Western Australian company, Fidelity Management Pty Ltd. Its Directors were Rex Paki and Gudmundur Fridriksson.

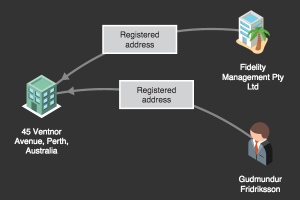

Fridriksson used the same Perth address as Fidelity Management Pty Ltd in records he submitted to the Investment Promotion Authority for Asigau (PNG) Holdings Limited, a company he owned with his wife, Tau Fridriksson. Initially the landholding company’s Secretary was Tau Fridriksson, according to Investment Promotion Authority records she was replaced on 1 July 1998 by Rex Paki.

Clearly a key player during the project’s start-up period was the Shareholder-Director-Secretary, Rex Paki, who was also the principal of Port Moresby firm Ram Business Consultants. Ram would go on to collect its own share of official condemnation from the Commission of Inquiry into the National Provident Fund, in addition to Public Accounts Committee and Auditor Generals Office investigations.

Despite having up and coming executives at the helm, PHLHC’s initial proposal for a luxury estate at Paga Hill was rejected by the Physical Planning Board in late 1996. The board noted, ‘proper procedures in relation to the processing of Planning applications were not followed’. This seemingly put an onion in the ointment, unless the application was approved, and the land rezoned, the Land Board could not lawfully issue an Urban Development Lease.

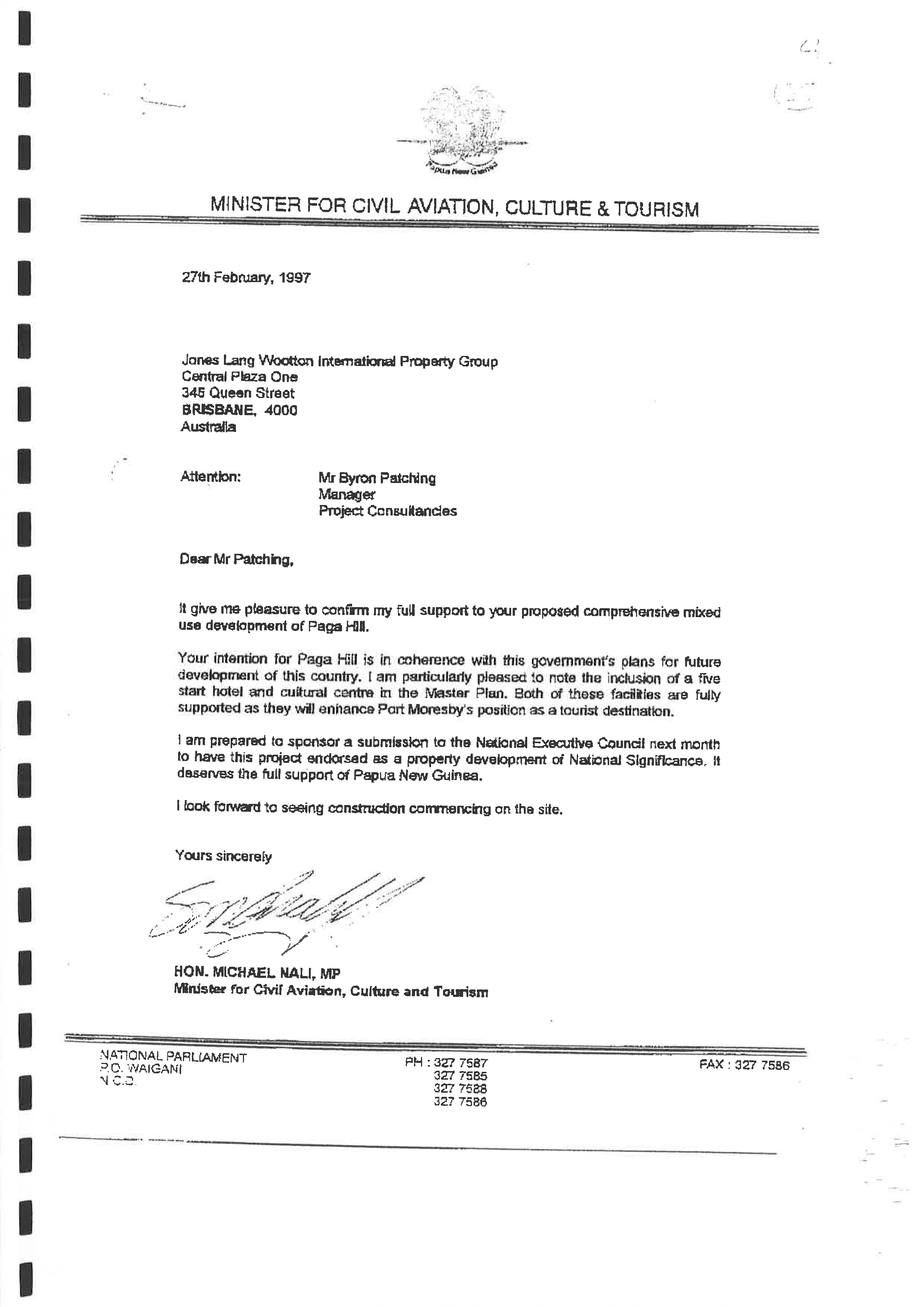

However, the company received a major boost in 1997, when its proposal obtained the backing of Michael Nali, the Minister for Civil Aviation, Culture and Tourism. On 27 February 1997 he wrote to PHLHC stating: ‘It give [sic] me pleasure to confirm my full support to your proposed comprehensive mixed use development of Paga Hill … I am prepared to sponsor a submission to the National Executive Council [Cabinet] next month to have the project endorsed as a property of National Significance. It deserves the full support of Papua New Guinea’.

Subsequently, Michael Nali acquired a 9% stake in PHLHC’s successor vehicle the Paga Hill Development Company (PHDC) through Kwadi Inn Limited, which Nali is the sole owner of. However, it should be underlined this occurred in December 2011. By then Nali had lost office.

Yet the importance of Nali’s involvement in 2011 can’t be underestimated. A towering figure from Papua New Guinea’s Southern Highlands, Nali is in business with some of the nation’s most powerful individuals.

Take the example of NIU Finance Limited. According to Investment Promotion Authority records [PDF], Nali’s company Kwadi Inn obtained a significant stake in this company during 2009, joining a select cast of executives and investors.

According to its last Annual Return, the company’s Managing Director is Peter O’Neill, Papua New Guinea’s Prime Minister. Peter O’Neill again appears as the largest shareholder in NIU, through his companies LBJ Investments Limited, and Paddy’s Hotel & Apartments Limited. Another notable shareholder in this enterprise is Piskulic Limited, a company wholly owned by Ken Fairweather, Member of Parliament for Sumkar.

There is no evidence on the public record to suggest either O’Neill or Fairweather have been involved in the Paga Hill Estate. Nevertheless, it is clear Nali circulates in powerful business circles.

And it goes further than this. It appears that Nali had direct business links with PHLHC’s Rex Paki and Felix Leyagon dating back to 1996-1997, the period when he agreed to sponsor the Paga Hill development as a project of national significance in Cabinet.

According to company records kept by the Investment Promotion Authority, on 11 November 1996, a company Waim No.54 Limited, was incorporated. Its two Directors were Rex Paki and Felix Leyagon. The company also had two equal shareholders, the Tourism Minister, Michael Nali and Mary Nali.

In addition to this, Waim No.54 Limited’s registered address was Ram Business Consultants, ADF Haus, Ground Floor, Musgrave Street, Port Moresby, National Capital District, Papua New Guinea. This is the same registered address employed by PHLHC.

If accurate, IPA records suggest Rex Paki and Felix Leyagon were Directors at a company owned by Michael and Mary Nali. Furthermore, Michael Nali’s company, Waim No.54, also shared PHLHC’s registered address.

During this same period, Michael Nali, in his Ministerial capacity agreed to sponsor PHLHC’s proposed Paga Hill property development in Cabinet as a project of national significance, a venture in which Rex Paki and Felix Leyagon were shareholders, with executive involvement from Gudmundur Fridriksson and Paki.

Public Accounts Committee alleges ‘corrupt dealings’

Of course, it cannot be deduced from these facts that the above parties were involved in any wrongdoing. However, in light of a subsequent Public Accounts Committee inquiry, which alleged that the land at Paga Hill was secured by PHLHC through ‘corrupt dealings’, this new link raises questions.

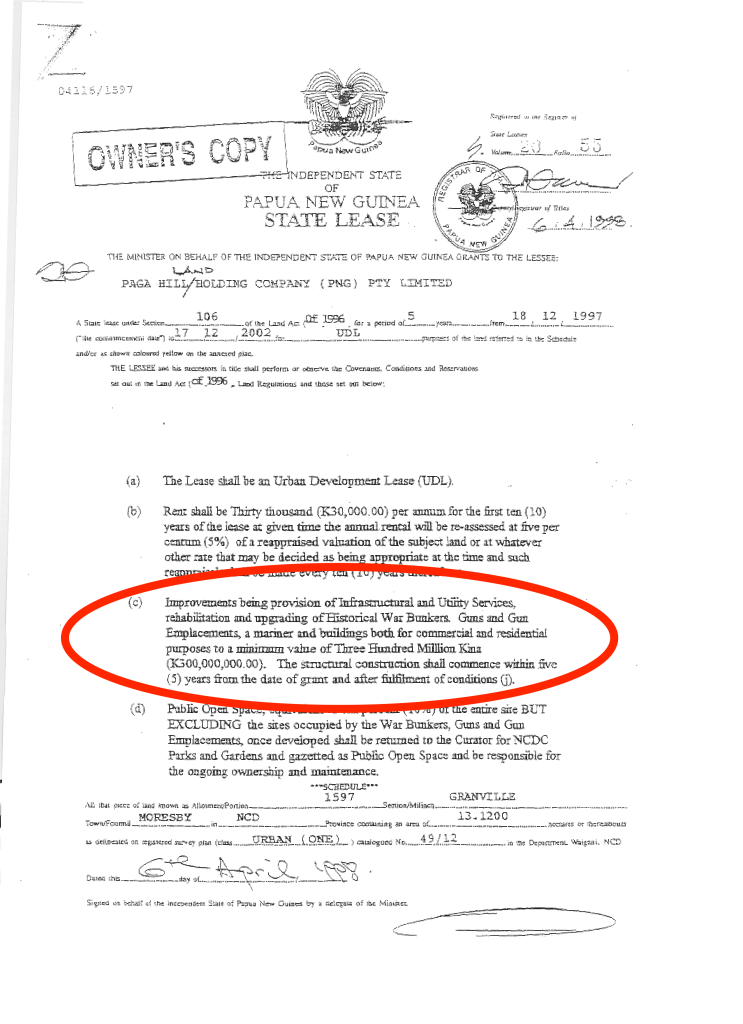

Underpinning the Public Accounts Committee’s concern was the circumstances under which the lease was obtained. For instance the Urban Development Lease was awarded to PHLHC when the land was still zoned open space. Before she recanted, Dame Carol Kidu observed this was in violation of the Land Act 1996, section 67, which declares, ‘a State lease shall not be granted for a purpose that would be in contravention of zoning requirements under the Physical Planning Act 1989, any other law relating to physical planning, or any law relating to the use, construction or occupation of buildings or land’.

Subsequently, PHDC was awarded a full 99 year Business Lease, despite the fact the improvement covenant set out in the Urban Development Lease was not completed as required.

The Public Accounts Committee claimed it was not surprised this covenant remained unactioned. It observed, ‘the Lessee cannot pay the Land Rental and has sought relief from that obligation, much less fund a development of the magnitude required’.

However, apparently this is not the only occasion that a company connected with Ram Business Consultants is alleged to have been involved in illegal land dealings. Those familiar with the Commission of Inquiry into the National Provident Fund Chaired by Judge Tos Barnett, may have had a touch of déjà vu when the name Waim was mentioned.

Ram Business Consultants, Waim No.92 and the NPF Commission of Inquiry

It was another holding company, Waim No.92 Pty Ltd, that was allegedly used to defraud the National Provident Fund – a transaction that saw one conspirator sentenced to six years imprisonment with hard labour. According to the Commission of Inquiry, controversial PNG businessman Jimmy Maladina was the ‘secret owner of Waim No.92 Pty Ltd the shares of which he initially owned through his wife Janet Karl, and an accountant Phillip Eludeme. Ms Karl’s share was later transferred to Phillip Mamando who resided at the Mr Maladina’s residence’.

The Commission of Inquiry alleges that ‘Mr Maladina was responsible for bribing Land Board chairman Ralph Guise and Lands Minister Viviso Seravo, to ensure Waim No.92 was granted the lease of the Waigani Land on very favourable terms’. It continues: ‘The records of the Land Board indicate it notified Waim No. 92 that it had been recommended as the successful applicant and on September 28, 1998, Waim No. 92 received notice that a corruptly reduced purchase price of K1,724,726.10 was payable before title would issue, with annual rent to be K17,000 (instead of the legally correct amounts of K2,866,000 and K143,000 respectively)’.

The Commission of Inquiry claims that Waim No.92 frontman Philip Eludeme acted as a key fixer, ‘prior to the Land Board hearing, Mr Eludeme had approached Minister Seravo seeking favourable consideration for Waim No. 92’s application and, at Mr Seravo’s request, had performed, free of charge, accountancy services for Minister Seravo valued at K100,000’.

According to the company’s annual returns for 1998, Waim No.92’s registered office during this period was Ram Business Consultants, ADF House. While its two shareholders cited above, Philip Eludeme and Phillip Mamando, similarly list their registered office as Ram Business Consultants, ADF House.

During 1998 Maladina’s alleged fixer, Philip Eludeme, was a director of the company Sulawei Limited, along with PHLHC shareholder, Felix Leyagon. Sulawei Limited’s registered address was again Ram Business Consultants, ADF House.

It would thus appear there were multiple links between two networks alleged to have been involved in similar style illicit land deals by the Public Accounts Committee and the Commission of Inquiry into the National Provident Fund, respectively.

The Paki Fridriksson split and the Inquiry into the Office of the Public Curator

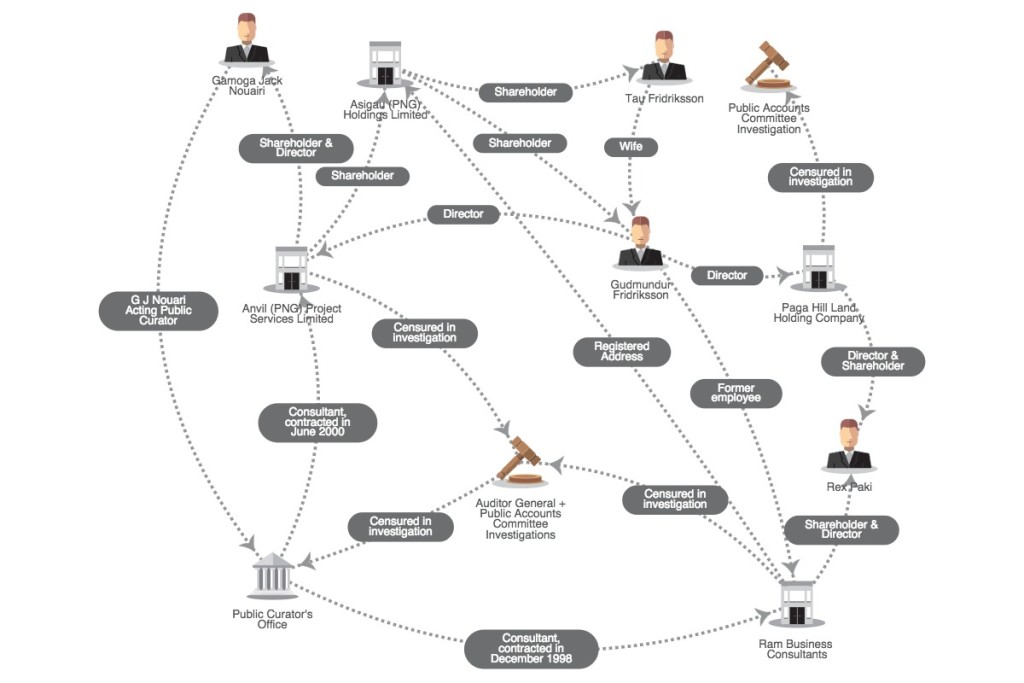

The original development vehicle was of course the PHLHC. However, the Auditor General notes in early 2000 its two Directors apparently part ways [PDF], with Gudmundur Fridriksson evidently leaving Ram Business Consultants where he was alleged to have been employed (Fridriksson is PHDC’s current CEO).

Fridriksson was then involved in setting up a number of companies including Anvil Legal Services Limited, Anvil Project Services (PNG) Limited, Anvil Commodities and Trading Limited, Anvil Marine Limited, Anvil Marketing Consultants Limited, and CCS Anvil Limited.

Anvil Project Services (PNG) Limited and CCS Anvil Limited have been censured in the course of inquiries conducted by the Auditor General, Public Accounts Committee and the Commission of Inquiry into the Department of Finance. Perhaps the most controversial of these companies is Anvil Project Services (PNG) Limited, which was awarded lucrative consultancy contracts with the Public Curator’s Office (shortly after Ram Business Consultants lost its contract with the same office).

This award wade made despite the fact the arrangement had been rejected by the Central Supply and Tender Board owing to no public tender – a procedure which is in violation of Papua New Guinea’s Public Finances (Management) Act 1995.

The contract went ahead anyway, although it is alleged [PDF] by the Public Accounts Committee and Auditor General, that payments were made out of private estates held on trust by the Public Curator.

According to company records kept at the Investment Promotion Authority, Gomoga Jack Nouairi, the Acting Public Curator at the time which the Public Curator and Anvil began working together, had a 30% stake in Anvil Project Services (PNG) Limited – the remaining 70% was owned by Gudmundur Fridriksson and his wife through the company Asigau (PNG) Holdings Limited.

Nouairi was also Director of Anvil Commodities and Trading Limited, in which Anvil Project Services (PNG) Limited had a 50% stake, and was a 50% owner of Anvil Legal Services Limited, along with Gudmundur and Tau Fridriksson.

Another company implicated in the inquiry into the Public Curator’s Office was Jac’o Business Consultants Limited, a concern owned by its principal Jack Naiyep. Despite being paid K1.5 million by the Public Curator’s Office, the Public Accounts Committee claims ‘there was no evidence that any formal procurement had ever taken place, nor was there any evidence of any formal contract’.

Naiyep and the Fridrikssons were business partners in a separate company they co-owned together, Anvil Business Services Limited. Naiyep also had a stake in Mamaku Mai No.3 Limited. Before the latter company was deregistered it was connected to the family of former Prime Minister Bill Skate. Also of significance is one of the company’s Directors, Paul Wagun.

It was a Paul Wagun who replaced Gomoga Jack Nouairi as Public Curator, and submitted evidence to the Public Accounts Committee and Taskforce Sweep contesting any wrongdoing by his office or Anvil (PNG) Project Services Limited. It cannot be confirmed this is the same Paul Wagun, however, given Jac’o Consultant’s role in the Public Curator’s Office, the overlap is concerning.

Sadly in a subsequent inquiry into this affair by Papua New Guinea’s anti-corruption agency, Investigation Taskforce Sweep, none of these crucial links between Fridriksson, Nouairi, Naiyep and Wagun were acknowledged in its case report, despite being freely obtainable from the Investment Promotion Authority company registry. When these flaws were noted by this author in a report published last year, Investigation Taskforce Sweep threatened to sue for defamation.

Another interesting company set up during this period under the Anvil stable, was Anvil Marine Limited. During its period of operation 2002-2005, the company was owned by Gudmundur and Tau Fridriksson, along with the father and son team, Tom Amaiu and Labi Alex Amaiu. Tom Amaiu is a former Member of Parliament, who was sentenced to five years prison for theft.

His son Labi Amaiu is the current Member of Parliament for Moresby North East, and has patronised PHDC, featuring prominently in the company’s promotional material. He can be seen in this video published by PHDC lauding Gudmundur Fridriksson. Amaiu states he would like to ‘congratulate and thank the CEO of Paga Hill development for a successful venture, this is what we call legacy, and I am proud to be part of that legacy’.

Fridriksson’s companies featured in a number of other inquiries during this contentious period, including the Commission of Inquiry into the Department of Finance. Nevertheless, public condemnation from Papua New Guinea’s anti-corruption agencies has not significantly impacted on PHDC’s grip over the land at Paga Hill.

Paga Hill Development Company’s Southern Highlands Connection

Part of PHDC’s success appears to be linked to its influential stakeholders. It will be recalled that the Urban Development Lease was originally awarded to PHLHC, a company jointly owned by Rex Paki, Felix Leyagon and Fidelity Management Pty Ltd. When the lease was converted into a 99 year Business Lease in 2000, the owner was a new corporate vehicle, PHDC.

The Public Accounts Committee in its inquiry drew attention to this – the recipient of any converted lease, it argued, should have been the initial owner PHLHC. At the time, PHDC was owned by Fidelity Management Ltd Pty, a holding company which shared a registered address in Perth, Australia with Gudmundur Fridriksson. But unlike PHLHC, Rex Paki and Felix Leyagon were not on the share register.

In 2005 ownership of the company changed hands, as Fidelity Management Ltd Pty’s shares were transferred to another vehicle, Anvil Holding Limited. At this time Anvil Holdings Limited was owned by George Hallit, along with Gudmundur and Tau Fridriksson. However, between 2008 and 2011 there were a series of further changes to PHDC’s ownership structure. By the end of it, the Fridrikssons’ apparently divested all their shares in the company. It was PHDC’s lawyer, Stanley Liria, who became the majority shareholder.

Originally from the Southern Highlands, Liria has published a number of legal texts. The first was launched in 2005 by Southern Highlands political heavyweight Peter O’Neill who informed the Post-Courier he would recommend to his ‘parliament colleagues that they buy the newly published book’.

Liria is also commercially linked to a number of high profile Southern Highland politicians. For instance, Liria is Director of Southern Highlands Holding Limited, along with former Minister, Michael Nali, who is also a PHDC shareholder via Kwadi Inn Limited. The sole shareholder of the holding company is the Southern Highlands Provincial Government.

In addition, there is Sharp Hills Investment Limited, a company fully owned by Southern Highlands Governor William Tipi, who entered parliament as an MP for Peter O’Neill’s People’s National Congress party. According to Sharp Hill’s company records, its registered office is Liria Lawyers, a firm which Stanley Liria is the principal of. William Tipi was also formerly a shareholder in Southern Highlands Holding Limited, presumably as a trustee for the provincial government.

Alongside Liria at PHDC is Michael Nali, who through Kwadi Inn, has acquired a 9% stake in the company – although this was reduced to 2% during April 2016. As we have already observed, Nali is in business with Papua New Guinea’s most powerful political players including Prime Minister O’Neill.

Curiously absent though is Gudmundur Fridriksson. Despite being the principal visionary and driver behind the project he has seemingly divested from the company, while retaining an executive role as CEO.

Nevertheless, given the current political gravity in Papua New Guinea, having backers with strong Southern Highlands credentials cannot have harmed the company over the past five years, as it has navigated significant public resistance to its real-estate venture.

Cold comfort

All this analysis is rather academic for former Paga Hill residents. Many had their homes, belongings, church and school destroyed through a number of demolition exercises between 2012-2014 (PHDC has only been directly linked to the first exercise in May 2012). The soul and life of the community is captured in a moving song they composed to commemorate the destruction:

As a result of the demolition exercise, the site is now being prepared for the luxury estate which Michael Nali lauded as Minister back in 1997. Twenty years on, as the development is promoted as a host site for APEC 2018, questions still linger over the land transactions that underpinned its inception and a number of executives involved in stewarding this project.

Given the systematic efforts being devoted to censoring a documentary film covering this controversial venture, one senses these questions may encroach on very powerful interests indeed.

Yet whatever happens with Paga Hill, audiences may sense the bell tolls for thee. As a real-estate venture Paga Hill is not unique or exceptional, even if its displaced residents are a very special group indeed.

Around the world cities are transforming through a process of creative destruction, or what geographer David Harvey calls accumulation by dispossession. They are becoming spaces moulded in the image of power, money, corruption and violence.

Indeed, the technical and often highly opaque character of urban governance is a breeding ground for abuse and inequality. It is a matter for wonks, bureaucrats and developers. It needs to be a space of popular, public participation.

The Opposition calls this to our attention. Of course, what we do to confront these dilemmas is the next urgent conversation to be had.