Western Tech Firms Sold Spyware to Myanmar’s Military Junta

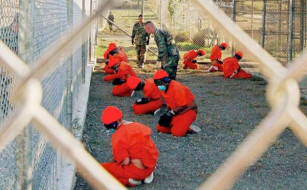

Since February 2021, civilian dissents in Myanmar has been violently crushed by the country’s self-appointed military junta, led by General Min Aung Hlaing. The widespread protests and civil demonstrations following the military coup have resulted in thousands of arbitrary detainments of activists, often aided by the use of dual-use security technology that is commonly used for non-military functions. Credible reports indicate that much of this technology was purchased prior to the coup from companies in Western democracies, likely aiding Myanmar’s long-term surveillance activities against ethnic minorities such as the Chin and Rohingya, before General Hlaing took power and refocused military aggression on dissidents of all ethnic backgrounds.

Following President Biden’s February announcement of economic sanctions on Myanmar, and a coalition of Western states issuing an arms embargo in March, technology trading has been substantially curtailed. However, General Hlaing was building up an arsenal of spyware throughout the former democratic regime, led by now-detained Aung San Suu Kyi. Largely bolstered by the 2015 power-sharing agreement, which allowed the military to retain 25% of parliamentary seats and substantial influence over the judiciary, defence systems and immigration policy, Myanmar’s military elite invested in civilian surveillance without much governmental pushback. However, up until the February coup, much of the resulting violence focused on securitised ethnic minorities in border regions, and the military concealed what has now been called genocidal atrocities as national security and counter-terrorist imperatives. Many of these activities garnered international condemnation, but lacked domestic opposition due to Suu Kyi’s delicate political compromise.

Now, General Hlaing’s military junta directs its surveillance state less discriminately. For example, several months before the coup, Myanmar’s Office of Cybercrime and national police, two institutions largely controlled by the military elite, ordered internet service providers to install spyware to intercept private communications throughout the country. In tandem with digital forensics software, which can hack mobile phones, these measures lead to mass arrests, torture and killings of civilian dissidents, many of whom were incriminated by virtue of being associated with public-facing activists. Companies from Canada, the United States, Italy, Sweden and Israel, among others, have sold spyware technology to Myanmar, reportedly unaware that it might be used with authoritarian disregard for human rights. Human rights advocates are now calling for a crackdown on the impunity that buyers in the global technology market enjoy, arguing that Western democracies have an obligation towards democratic principles and must hold corporations to account.

“The Pegasus Project” is an investigative initiative by the Washington Post to highlight the “expanded use of digital surveillance by governments worldwide” and its violent effects. This unfettered global industry, dominated by multinational technology corporations and their public or defence sector deals, has been at the epicentre of many human rights violations in the past decade. For example, spyware produced by an Israeli company called NSO Group was used to hack over 50,000 phone numbers across 50 states, many with long records of atrocities against civilians. NSO Group claimed that this spyware (called “Pegasus”, after which the investigation takes its name), was intended only for crime control and counter-terrorism measures, though demonstrated no concerted due diligence as to the application of this software in the many countries where it was sold. In another instance, a middleman company called Digitary China orchestrated a sale of American-made surveillance technology from Austin-based company Oracle, to Chinese police. Several provincial police departments in China subsequently used Oracle technology to surveil civilians suspected of criminal activity based largely on their ethnic profile.

The absence of a comprehensive export controls regime that monitors and regulates the spyware industry means that many of these exchanges are legal. While Myanmar’s surveillance operations violate a suite of domestic and international laws that protect civilian’s due process rights and prohibit ethnic discrimination and extrajudicial detainment, there is little accountability from the companies that supplied this technology. Two approaches could potentially defend the parameters of safe spyware use: first, state accountability from the company’s origin country, and second, corporate due diligence before and after sale. The United Nations Guiding Principles for Business and Human Rights could be a good place to start building state accountability for better monitoring of the private export of potentially dangerous technology. This international agreement requires signatory states to “provide effective guidance to business enterprises on how to respect human rights throughout their operations,” in order to ensure that every point in the supply chain complies with the principles of international human rights. Corporate accountability, on the other hand, would require tighter domestic export laws that hold corporations to a reasonable measure of due diligence, both prior to and after the sale of spyware technology. However, this kind of due diligence is subject to grave discrepancies and oversights. NSO Group, for example, cannot sell Pegasus technology without the buyer first obtaining a licence from the Israeli Defense Ministry, which states that all buyers must be governmental entities with the sole purpose of fighting crime and terrorism. The consensus among state crime experts is that at least 170 million people (though likely much higher) were murdered by their governments in the 20th century. It is therefore a major blind spot in international law and corporate ethics that states should enjoy presumed legitimacy in their employment of powerful technology, including not only surveillance technology, but also that which has unequivocally singular functions. Arms trading has been subject to international regulation since about 2014, when the United Nations passed the Arms Trade Treaty and mandated that signatories (heads of state) self-report all arms deals and compliance mechanisms to protect civilians. Notwithstanding its meagre enforcement capacity, the treaty nevertheless creates a general code of conduct for partner states around the world, and allows for international condemnation, and even summons to the International Court of Justice, if a state is accused of violating the treaty’s terms. Imperfect, but better than nothing.

Legislation of this sort could protect populations subject to violent state surveillance in two respects: first, it requires states to monitor the functions of imported and exported spyware, and second, it puts normative pressure on corporations to more seriously consider the applications of their products. These outcomes could seriously obstruct the violations of human rights that often attend the global distribution of spyware technology.

Works Cited:

Al Jazeera’s 101 East. “Myanmar: State of Fear” (video). 16/5/21. Accessed 1/22. https://www.aljazeera.com/program/101-east/2021/6/16/myanmar-state-of-fear

Amnesty International – Arms Control. “Reckless arms trading devastates lives. Weapons and ammunition are produced and sold in shockingly large quantities.” Amnesty International. Accessed 1/22. https://www.amnesty.org/en/what-we-do/arms-control/

Bauchner, Shayna. “Decades of Impunity Paved Way for Myanmar’s Coup.” Human Rights Watch. 7/12/21. Access 1/22. https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/12/07/decades-impunity-paved-way-myanmars-coup#

Feldstein, Steven. “Governments Are Using Spyware on Citizens. Can They Be Stopped?” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. 21/7/21. Accessed 1/22. https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/07/21/governments-are-using-spyware-on-citizens.-can-they-be-stopped-pub-85019

Hvistendahl, Mara. “How a Chinese Surveillance Broker Became Oracle’s ‘Partner of the Year’.” The Intercept. 22/4/21. Accessed 1/22. https://theintercept.com/2021/04/22/oracle-digital-china-resellers-brokers-surveillance/

OCCRP. “Myanmar Security Forces Using Western Surveillance Tech Against Civilians.” Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. 14/6/21. Accessed 1/22. https://www.occrp.org/en/37-ccblog/ccblog/14621-myanmar-security-forces-using-western-surveillance-tech-against-civilians

Pamuk, Humeyra and Holland, Steve. “Biden announces new sanctions against Myanmar generals after coup.” Reuters. 10/2/21. Accessed 1/22. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-myanmar-politics-usa-sanctions-idUSKBN2AA2CJ

Potkin, Fanny and McPherson, Poppy. “How Myanmar’s military moved in on the telecoms sector to spy on citizens.” Reuters. 19/5/21. Accessed 1/22. https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/how-myanmars-military-moved-telecoms-sector-spy-citizens-2021-05-18/

Priest, Dana; Timberg, Craig and Mekhennet, Souad. “Private Israeli spyware used to hack cell phones of journalists, activists worldwide.” The Washington Post. 18/7/21. Accessed 1/22. https://www.washingtonpost.com/investigations/interactive/2021/nso-spyware-pegasus-cellphones/?itid=lk_inline_manual_3

Scully, Gerald W. “Murder by the State.” NCPA Policy Report. 9/97. Accessed 1/22. https://www.ncpathinktank.org/pdfs/st211.pdf

Tisdall, Simon. “Myanmar’s top general Min Aung Hlaing is strangling a democracy. What will the west do about it?” The Guardian. 5/12/21. Accessed 1/22. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/dec/05/myanmars-top-general-min-aung-hlaing-is-strangling-a-democracy-what-will-the-west-do-about-it

UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. “Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.” United Nations. 2011. Accessed 1/22. https://www.ohchr.org/documents/publications/guidingprinciplesbusinesshr_en.pdf

UN News. “Myanmar military leaders must face genocide charges – UN report.” United Nations News. 27/8/18. Accessed 1/22. https://news.un.org/en/story/2018/08/1017802

Wade, Francis and Albert, Eleanor. “How Myanmar’s Military Wields Power From the Shadows.” Council on Foreign Relations. 2/10/17. Accessed 1/22. https://www.cfr.org/interview/how-myanmars-military-wields-power-shadows

[ISCI Intern Article]