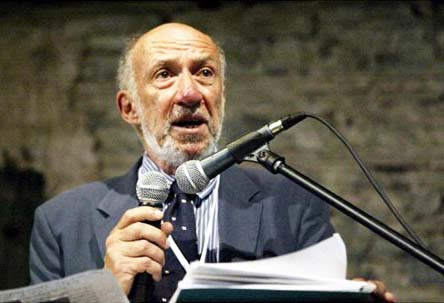

Richard Falk Responds to ‘Fast Times in Palestine: A Love Affair with a Homeless Homeland’ by Pamela Olson

I realize without knowing it that I have long waited for this book, although I could not have imagined its lyric magic in advance of reading. It is a triumph of what I would call ‘intelligent innocence,’ the great benefits of a clear mind, an open and warm heart, and a trustworthy moral compass that draws sharp lines between good and evil while remaining ever sensitive to the contradictory complex vagaries of lives and geographic destinies. Pamela Olson’s exhibits an endearing combination of humility and overall emotional composure that makes her engaged witnessing of the Palestinian ordeal so valuable for me, and I believe it would be for others.

Early on, she acknowledges her lack of background with a refreshing honesty: “So green and wide-eyed, I wandered into the Holy Land, an empty vessel.” But don’t be fooled. Olson, who had recently graduated from Stanford, almost immediately dives deeply into the daily experience of Palestine and Palestinians, with luminous insight and a sensibility honed on an anvil of tenderness, truthfulness, and a readiness for adventure and romance. Upon crossing the border that separates Israel from the West Bank, enduring some routine yet always scary difficulties at the checkpoint, she find herself in the Palestinian village of Jayyous, which is not far from the Palestinian city of Jenin. Her first surprise is to be the recipient of welcoming warmth by the villagers whose hospitality makes her feel almost immediately as if she is on a homecoming visit to Stigler, the small town in eastern Oklahoma where she grew up and her family still lives. Almost at once Olson finds herself in the midst of a social circle in Jayyous that picks olives during the day and sits around in the evening puffing on a nargila (water pipe) while conversing about the world on the porches of villagers.

Olson’s authenticity pervades the book, whether it is a matter of adoring the cuisine or acknowledging her infatuation with this or that Palestinian young man who crosses her path. She struggles to speak a bit of Arabic, reads up on the struggle, and stays alert. The style of the book is an enchanting mixture of personal journal, travelogue, political primer of the conflict, and a coming of age novella that is full of emotion. She writes with clarity, humor, and self-scrutiny (in a tone of almost asking herself ‘who is this girl from rural Oklahoma who is experiencing this extraordinary encounter with people and the sad conditions of their lives?’).

Through the whole of her Palestinian experience, Olson impressively remains open to her Israeli friend, Dan, as well as to an Christian appreciation of the Holy Land, not as a believer but as someone whose identity was formed in a religiously Christian community. When she tells Dan about how disturbed she has become by what the way the occupation impinges on Palestinians he reminds her of Israeli grief and distress. Dan’s words: “Last year there was a suicide bombing practically every week, it was…unbelievable. The mall we went to yesterday was bombed last year. Three weeks ago a killed twenty people in a restaurant in Haifa. Just innocent people having a meal.” Olson’s response is characteristically empathetic: “I sighed and looked out over the water. What I had seen in the West Bank was terrible, but there was another side of the story, after all. I tried to imagine the horror of people sitting around having a meal, and then all of a sudden—“ The book is sensitive to the tragic experiences of both peoples despite its focus on what occupation means as an existential reality of Palestinians entrapped for more than 45 years in the West Bank, and how their extraordinary qualities of humane coping make Jayyous and Ramallah so inspirational for her, instilling a longing to return to share the dangers and deprivations, which are more powerfully satisfying than the pleasures of ‘freedom.’ I am reminded of a friend from Gaza, a leading human rights activist, whose family has been living in Cairo in recent years, who tells me that when he plans a vacation, his university age children who are studying abroad, insist on Gaza rather than Paris or London.

One of the most moving chapters in the book is a description of the visit of Olson’s mother and stepfather. She had pressured them to come so that they might understand better than from her many letters home so that “they would never have to wonder whether I had exaggerated the beauty or the horror.” Olson’s deep appreciation of the beauty of the West Bank setting is also a part of the originality of her vision of the place as she is not primarily seeing the people or the countryside through a political optic. Because they kept delaying a visit, Olson confided that “Finally, I said to Mom, ‘If you love me, you’ll come see what my life is like over here.’” And she did, and what is more, although this was her first trip outside of America, saw what was to be seen with fresh eyes. This experience produced tearful reactions summarized by her mother’s response to the treatment at a typical crossing: “’Good Lord,’ Mom said, ‘How can this be happening over here and no one in America even knows or cares?’” Is not this the question we should all have been asking for decades? During the visit, they also go to Israel, and spend much time touring the Christian sites in and around Jerusalem that are particularly meaningful to her religious mother.

The book does not cover the whole of the conflict, its history or what has taken place in recent years, which merely is an intensification of what Olson reports upon. There is no attempt to be systematic, but the essentials of the occupation do emerge, especially the encroachment of the separation wall, the settlements, and checkpoints on what it means for a Palestinian to live day by day under an occupation that has gone on since 1967, and shows no sign of ending in the foreseeable future. And when Olson inserts information about the situation and the relevance of international law and elementary morality, she is accurate, concise, and perceptive. She also is honest enough not to suppress her emotional responses to some extreme situations, such as the surrounding of the small Palestinian city of Qalqilia by a 25’ high wall that confines its 40 thousand inhabitants day and night:

“The town has been turned into one giant prison. It was the most insane and dispiriting thing I have ever seen.”

Later she observes that Qalqilia used to be a very pleasant town, that was now cut off from some of the richest agricultural land in the region, and that this wall is not really connected with ‘security,’ as claimed, because there remain numerous ways to enter Israel covertly if the motivation exists.

In the end what gives the book its special value is the compelling credibility of her “love affair with a homeless homeland,” a sub-title that says it all! It is one thing to lament the suffering and humiliation of the Palestinians or to condemn the cruelty and harshness of the Israeli occupation, but it is quite another to be able to observe these defining realities, and yet see beyond, to a proud and gracious people that are playful and manage to live as vibrant as circumstances allow. It is this combination of at once feeling the Palestinian hurt while celebrating the warmth and genuineness of the Palestinian embrace that allows a reader to achieve what I had previously thought to be impossible without an immersion in the place. Olson is an 21st century instance of how a reassuringly normal American woman might best visit the Arab world. She is intensely curious, with a gift for observation and dialogue, and a sensibility that is not afraid of danger or to acknowledge shades of gray or to register her disappointments with others, and above all with herself. Her own evolution is also relevant, from a ‘Bible-centric’ youth in Oklahoma to a scientific oriented skepticism to this wonderfully caring person who managed to have this incredible ‘love affair’ occupied Palestine, amid the ruins. In her words, “I couldn’t imagine a better university of human nature.”

Obviously, Pamela Olson is blessed with talent. A girl from rural Oklahoma who had to struggle to find the funds to attend college does not make it to the likes of Stanford very often where she majors in physics and political science, nor does the typical graduate defer the job market, and go about exploring the world to find out what it is like, and how best to live her life. It is thus not as surprising as it might otherwise seem that after her experiences in Palestine, Olson returned to work for a ‘Defense Department think tank,’ and found it ‘educational but disillusioning.’

I have the following daydream: If everyone in America could just sit down quietly and read this book, there would be such an upsurge of outrage and empathy that the climate of opinion on the Israel/Palestine conflict could be changed for the better even within the polluted air that now prevails within the Beltway. At the very least, everyone who can should read the book, and if my reactions are shared, give a copy to friends and urge them to spread the word that we should not subsidize and tolerate any longer ‘a homeless homeland.’ As a close Palestinian friend in Jayyous, Rania, tells her, “’Imagine if there was no occupation! Palestine would be like paradise.”

The book can be pre-ordered from Amazon. It will be available in mid-March. I urge you to do so!