Police Room 619

‘September 77, Port Elizabeth, weather fine. It was business as usual in police room 619.’

Peter Gabriel, ‘Biko’

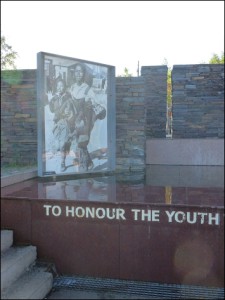

When I think back on how I became aware of Apartheid in South Africa, I realise it hangs on two events in the mid-1970s. In 1976 school children who were boycotting their schools because lessons were delivered in Afrikaans were protesting on the streets of Soweto, Johannesburg. The police opened fire killing 12 year Hector Peterson. The photograph of an older youth, Mbuyisa Makhubo, face lined with grief, running and carrying Hector’s body with Hector’s crying sister alongside became one of the iconic images of that whole conflict.

A year later and 1100 kilometres away, Black Consciousness Movement leader Steven Biko was arrested in Grahamstown and brought to Port Elizabeth for interrogation. The Eastern Cape Security Branch of the South African police had hired the top floor, the sixth, in a private office building, the Sanlam Building, on Strand Street near the docks and it is there they brought people for interrogation and torture. As the Truth and Reconciliation Commission confirmed, Biko’s head was rammed into the wall of the interrogation room by the security police who then manacled him to the metal grill of the door and left him there, unconscious and foaming at the mouth. They then tried to revive him by putting him in a bath of cold water. He was later taken, naked and manacled, in the back of a police vehicle all the way to Johannesburg where he later died. The story of Steven Biko became another milestone in that developing nightmare and is caught in Peter Gabriel’s haunting and yet uplifting song.

In October 2012 I was in Port Elizabeth for the first time in my life. A few days before I had seen the memorial where Hector Peterson had been shot dead. Now I wanted to see police room 619. I went with Janet Cherry, who as an activist had herself been interrogated there before being detained for a year. She warned me to expect the worst. Sure enough, the building was derelict, with almost every window broken and the front doors padlocked. Through the dirty glass of the front doors could be seen a sign indicating that the building had been renamed ‘Steven Biko House’, but there was nothing else to pick this building out from others around, except perhaps its greater state of dereliction. We walked round the building, trying to get through the fence at the back. But there was no way through. Even if there had been, it was unlikely that we could have got in the back entrance and up the stairs, the way in which most of those arrested had been brought in for interrogation.

We were about to leave when Janet had an idea. She went into the shop next door and talked to the shopkeeper. A few minutes later he emerged carrying the keys to the padlock. We were in! We climbed over the rubble and up the six flights of stairs and we were there on the sixth floor. There was rubble and broken glass and many of the doors were off their hinges and lying on the floor. A few of the doors had numbers above the lintel, but not enough to tell us what the pattern was in the maze of rooms. We wandered around a number of times looking for clues, but none jumped out. Janet was understandably quiet. But she could not remember which room was the right one. Fair enough; I suspect that under interrogation the last thing you would be thinking about is the layout of the building so that you could bring a visitor back there over three decades later. But finally, she did narrow it down. She remembered that Room 619 was at the front of the building and there was only one such room to be found that had an adjacent restroom with a bath. We stood in silence.

This was a strange shrine, a ghost of its former self. And yet there were surely ghosts there. Not just Biko, but also George Botha, Lungile Tabalaza and Siphiwo Mtimkulu. George Botha had died in 1976 after ‘falling’ down the main stairwell. Lungile Tabalaza had died ‘trying to jump’ from a window to a building across the street in 1978. Siphiwo Mtimkulu was tortured and poisoned in the building in 1982 before being shot in the head. His body was never found, but was presumably burnt by his interrogators.

To quote Easter Cape novelist J.M. Coetzee completely out of context it is a disgrace that a place so connected with those who suffered on the road to liberation has been dishonoured. Fair enough that the new South Africa has contemporary problems to deal with and one cannot begin to solve them with eyes constantly looking backwards to the past. At the same time, it is feasible to maintain that they cannot be solved by forgetting the past, burying the memory of such important events under rubble, glass and dust.

It is clear that at some point someone realised this; hence the change of name of the building in honour of Steven Biko. Yet that sign is hardly visible now behind the dirty glass of the padlocked front door. I suppose that’s fitting in a way, as if the sign is ashamed to show its face in such shabby attire. Yet, if there was a point when the memory was preserved, why is that no longer so? Why has the place been allowed to go to ruin? The ANC was not particularly enamoured of Biko and his Black Consciousness Movement. But it would be awful to believe that they were so churlish as to carry that grudge now. Besides, three others died as a result of the actions of the police in that building and they were not all Black Consciousness Movement people.

If, as Milan Kundera wrote in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, remembering is a form of forgetting, then it is a poor bargain that has been made in contemporary South Africa. It is right that ‘sanctioned memory’ puts Hector Peterson’s story out in the open so that future generations will not forget. But the cost of that should not be that the sacrifice of Steven Biko is not mentioned and honoured.

If, as Milan Kundera wrote in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, remembering is a form of forgetting, then it is a poor bargain that has been made in contemporary South Africa. It is right that ‘sanctioned memory’ puts Hector Peterson’s story out in the open so that future generations will not forget. But the cost of that should not be that the sacrifice of Steven Biko is not mentioned and honoured.