State Crime in UK hip-hop: a soundtrack to the struggle

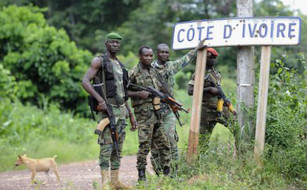

“This track is not an attack upon the American people. It is an attack upon the system in which they live. Since 1945 the United States has attempted to overthrow more than 50 foreign governments. In the process the US has caused the end of life for several million people; and condemned many millions more to a life of agony and despair.”

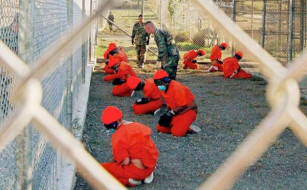

These words introduce Obama Nation, a track from Lowkey’s 2011 album Soundtrack to the Struggle. Their delivery – spoken, rather than rapped – identifies them as a warning that the lyrical themes to come will be neither familiar nor comfortable. As Lowkey says on Obama Nation part II, “I say things other rappers won’t say/’cos my mind never closed, like Guantanamo Bay” (see below at 3 mins 30):

Hip-hop has its roots in social injustice, oppression and state crime. It has provided voice to oppressed groups (notably, but not exclusively, to black Americans – see, for example, Public Enemy’s 1988 album It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back and NWA’s self-explanatory Fuck Tha Police from Straight Outta Compton and a forum for articulating alternative perspectives on issues that official state policy renders taboo. Great art, with hip-hop as with any form, derives its greatness from the importance of drawing attention to issues of significance.

Although many artists are either unconcerned with or have lost sight of the struggles and circumstances in which hip-hop was forged, some others choose – often at the cost of commercial success – to use hip-hop to approach more difficult subject matter.

Lowkey – Obama Nation

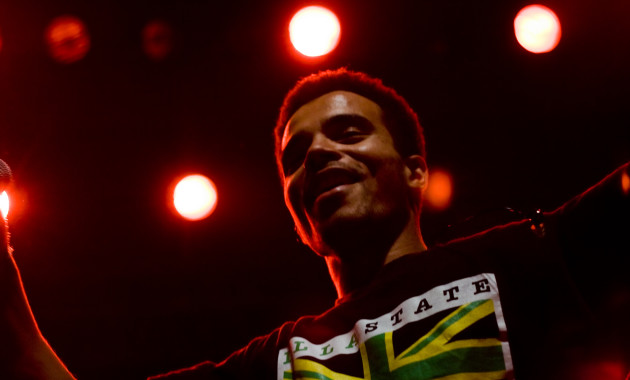

Lowkey‘s lyrics, whether or not the listener agrees with their content, are thought-provoking. Commercially successful hip-hop today often involves less meaningful boasts of materialistic, misogynistic and violent tendencies. Akala, another British rapper, warns against seeing these themes as cultural expression (see below at 1:16); and challenges their greater significance: “you can boast about your platinum chain and your diamond rings/while kids in Sierra Leone keep on losing limbs” (1:29):

Obama Nation part II is worth focusing on briefly. The introductory sequence includes a video clip from the studio of the Glenn Beck Radio Show. Beck and his co-presenter attempt to belittle the content of Terrorist?, another Lowkey track from Soundtrack to the Struggle. Terrorist? itself sees Lowkey challenge the manner in which concepts of ‘terror’ and ‘terrorism’ have come to exclusively denote anti-Western violence.

It is significant that Beck feels the need to react, however clumsily, to the work of a British rapper. Lowkey, before his recent retirement from music, was invited by Hugo Chavez to perform in Venezuela due to his outspoken views on US ideology and foreign policy. Beck himself is as vocally supportive of US ideology and foreign policy as it is possible to be – a proponent of what Lowkey described as “the system in which [the American people] live”.

The point is that the ‘system’ – whether American or otherwise – moves to reassert itself when threatened. Lowkey claims to have been charged with an offence of encouraging terrorism under section 1 of the Terrorism Act 2006. There is nothing in Lowkey’s music that could reasonably be construed as such – in fact, if Lowkey is intolerant in any sense, his intolerance is of the tendency for dogmatic State policies to go unquestioned and untested by the States’ respective populations.

Akala – ‘Fire in the Booth (part 1)’ – Charlie Sloth’s radio show (BBC 1extra)

Akala’s lyrics concern many issues of State Crime. Among among them are the questionable justifications sometimes put forward by states for acts of military intervention (such as at 00:50): “That’s right – we are the feminists/For the women of the world kill terrorists/Liberate them from their burkas/They’ll feel more free with their children murdered”.

Mic Righteous – ‘Fire in the Booth (part 1)’ – Charlie Sloth’s radio show (BBC 1extra)

It is unsurprising that Mic Righteous’ invitation to “free Palestine” does not escape censorship by the BBC (see above at 3:00); but from 2:41 to 3:26 he discusses the difficulty of reconciling commercial success with his desire to address the failings of state policy, such as the inadequacy of international efforts to relieve flooding in Pakistan.

A Common ‘Conscious’ Attitude

Akala, Lowkey and many other British artists others defy convention by electing not to speak solely from their own cultural or social perspective. Their genre, which they describe as ‘conscious’ hip-hop, actively dissociates itself from single perspectives and frequently rejects points of view prescribed, from above, by the state. Lowkey is of mixed British and Iraqi heritage; English Frank is white British; and Mic Righteous was born in England to Iranian parents. Akala describes himself on Find No Enemy as “second generation black Caribbean and half white Scottish, whatever that means” – commenting that “lately I feel confused by the boxes/’cos all they seem to do is breed conflict”.

The fact that there is a common, ‘conscious’ attitude that pervades these artists’ different religious, cultural and ethnic backgrounds is remarkable. It is also remarkable that the unconventional message delivered by this collective attitude simultaneously resonates with an equally diverse audience of primarily young people.

Hip-hop music rarely tackles State Crime with profit in mind; and it is a bold choice for the individual artists – many of whom are from disadvantaged social backgrounds – to forego the possibility of commercial success in order to say something more important.

“Some music”, observes Mic Righteous, “we make for the shelves/But this music, dog, we make for ourselves.”

Stuart Reid is a dispute resolution solicitor and an LLM student specialising in dispute resolution and public international law.