Habib Souaïdia and Algerian state crime

In April 2015, Habib Souaïdia made a rare sortie into the public domain, publishing a serious indictment of the role of Algeria’s secret intelligence service, the Département du Renseignement et de la Sécurité (DRS), in recent terrorist activities in Algeria and the attempted destabilisation of neighbouring states.

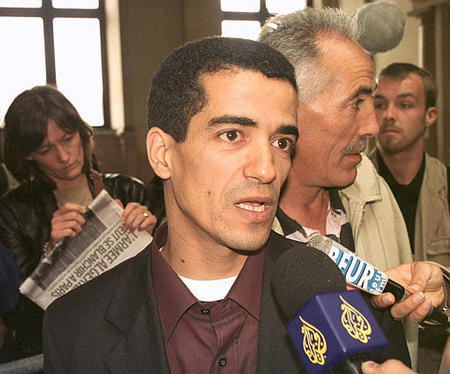

Habib Souaïdia, is a 46 year-old Algerian (born, in Tebessa, Algeria, in 1969) described by Wikipedia as “an Algerian writer and former member of the Algerian army’s Special Forces.” That is not incorrect, but it is misses the substance.

Souaïdia enlisted in the Algerian army in 1989 and became a junior officer (second lieutenant) and parachutist in the elite Special Forces. In the 1990s, he witnessed the atrocities being committed by the Algerian army and DRS against both known and suspected Islamists and, more significantly, innocent Algerian civilians, many of whom were massacred in cold blood by the DRS’s killing squads. The overall commander of the DRS at that time, General Mohamed “Toufik” Mediène, is still, to this day, the DRS boss. Until the restructuring of the DRS and his relative political demise in 2013, Mediène was without doubt the most powerful man in Algeria.

In 1995, Souaïdia was sentenced to four years imprisonment on trumped up charges. “They arrested me to silence me,” he later wrote, swearing that when he was released he would expose to the free world what his state had been doing.

He was released in 1999 and in 2000 obtained a passport and flew to France, where he tried to interest journalists in his story, which was a serious embarrassment to the French government. Both Presidents Francois Mitterrand and Jacques Chirac had backed the Algerian regime in its war against the Islamic fighters.

However, in November 2000 he was granted his request for political asylum. The following year (2001), he published his memoirs: La sale guerre. Le témoignage d’un ancient officier des forces spéciales de l’armée algérienne,1992-2000 (The Dirty War: The testimony of a former officer of the special forces of the Algerian army, 1992-2000″.[1]

When Souaïdia broke his silence in 2001, he wrote: “When I enlisted in the army in 1989, I never imagined that I would be a direct witness of the tragedy that has befallen my country …

“I have seen my colleagues set fire to a boy of 15, who burned like a living torch. I have seen soldiers slaughtering civilians and blaming ‘the terrorists.’ I have seen senior officers murdering in cold blood simple people who were suspected of Islamic activities. I have seen officers torturing Islamic activists to death. I have seen too many things. I cannot remain silent. These are sufficient reasons for breaking my silence.”[2]

La Sale Guerre is in many respects the most important work to come out of Algeria’s Dirty War. The reason for that is because the Algerian regime, in the personage of General Khaled Nezzar, the Defence Minister at the time of the atrocities, sued Souaïdia for libel. In a long, high profile case in a Paris court, Nezzar lost his case, thus rubber-stamping Souaïdia’s testimony as the correct and truthful account of the massacres. As the years have gone by, multiple works, notably An Enquiry into the Algerian Massacres (1999)[3], have affirmed the status of Habib Souaïdia’s testimony and the criminal roles of the Algerian regime, its army and DRS.

La Sale Guerre is in many respects the most important work to come out of Algeria’s Dirty War. The reason for that is because the Algerian regime, in the personage of General Khaled Nezzar, the Defence Minister at the time of the atrocities, sued Souaïdia for libel. In a long, high profile case in a Paris court, Nezzar lost his case, thus rubber-stamping Souaïdia’s testimony as the correct and truthful account of the massacres. As the years have gone by, multiple works, notably An Enquiry into the Algerian Massacres (1999)[3], have affirmed the status of Habib Souaïdia’s testimony and the criminal roles of the Algerian regime, its army and DRS.

The conclusion of La Sale Guerre is that the “main problem [in Algeria] is injustice”. Souaïdia wrote: “If an end is put to the injustice, peace will come to Algeria. Therefore it is necessary to stop the corrupt individuals who are continuing to rob the huge assets of the Algerian people.”

That was in 2001. Today, the crimes of the Algerian regime are perhaps even greater, not so much in terms of killing their own innocent citizens, but in terms of “injustice”, the abuse of human rights and the endemic, oligarchic corruption of a regime that is continuing, perhaps on an even greater scale, to rob the Algerian people of their “huge assets”.

It is against the background of Algeria’s current political and oil-price-driven economic crises that Souaïdia has published his latest indictment of the Algerian regime and its secret intelligence service, the DRS.

The article, entitled “De l’assassinat d’Hervé Gourdel à la destabilisation tunisienne: manipulations et intox des services secrets algériens”, was published by Algeria-Watch on 27 April 2015.

If only half of Souaïdia’s article is true, then it has serious implications for security throughout most of North Africa.

The obvious question, however, is how much of Souaïdia’s article is true? I can give two assurances. The first is that almost everything that Souaïdia has said and written since 2001, barring a few largely irrelevant details, has been proven to be correct. Souaïdia thus has credibility. The second assurance I can give is that both my own research, as well as a number of corroborative sources, tends to verify all six of Souaïdia’s main claims.

The only noticeable error relates to the death of hostages and terrorists at the Tiguentourine gas facility (In Amenas) in January 2013, when he says that thirty-eight Western hostages, an Algerian and twenty-nine terrorists, were all killed by fire from DRS helicopters. As we now know from the details of the In Amenas inquest held in London recently, not all the hostages were killed in the helicopter assault to which Souaïdia is referring. Although several of the hostages were killed by fire from the Algerian army, the fire seems to have come more from troops on the ground rather than the helicopters.

The reason for this error is that Souaïdia obtained details of what happened at Tiguentourine from his own sources and either directly or indirectly from Algerian soldiers who were there. Many of them saw rockets being fired from the helicopters and assumed that the rockets caused the explosion of the vehicles carrying both terrorists and their hostages. In fact, the inquest evidence indicates that the explosions came from bombs (explosives) being carried by the terrorists in the vehicles, which were probably detonated either by the terrorists or by army ground fire that was being directed into the vehicles and not by rockets fired from the helicopters.

Souaïdia’s article covers six broad issues:

(1) That the DRS was behind the abduction and murder of French tourist Hervé Gourdel in September 2014.

(2)How the DRS prolonged their manipulation of Islamist violence after the end of the civil war of the 1990s.

(3) The relationship between hostage taking and the creation of new armed groups.

(4) Tension between the army and DRS.

(5) The involvement of the DRS in the destabilisation of Tunisia.[4]

(6) Concluding thoughts on the re-emergence of the DRS.

The murder of Hervé Gourdel

Souaïdia alleges that the abduction and beheading of Hervé Gourdel in September 2014 was not the work of the Islamic State (IS), or Daesh, as it is known locally in Arabic, as officially claimed, but the work of Algeria’s DRS, and in the same pattern as its manipulation of Islamist armed (“terrorist”) groups over the previous 20 or more years.

Frenchman Hervé Gourdel (55) was kidnapped by an extremist group in Algeria’s Kabylie region on 21 September and beheaded three days later on 24 September.

Gourdel, an alpine guide from Nice, was starting a trekking holiday in the mountainous Djurdjura National Park in Tizi Ouzou wilaya. He arrived in Algeria on 20 September and spent that night at a ski lodge near the town of Tikjda in the Djurdjura. The next day, he was driving through the heart of the Djurdjura Mountains with two Algerian companions near the village of Ait Ouabane when he was stopped by a group of armed men. The gunmen released the Algerians, who alerted the authorities, and took Gourdel.

The next day, an online video showed Gourdel flanked by masked, armed men. In an address directed to France’s President François Hollande, a member of the group threatened to kill Gourdel unless France’s airstrikes against IS militants in Iraq were halted within 24 hours.

The group said it was answering a call by IS spokesman Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, who, in a 42-minute audio statement released on 21 September, urged followers to kill Americans and Europeans, “especially the spiteful and filthy French”.

The kidnappers said they were members of the Algerian group Jund al-Khilafah (en Algérie), also known as Soldiers of the Caliphate. The group, believed to be an Al Qaida splinter group, is said to have pledged allegiance to the IS. It had announced itself in Algeria on 13 September, with its leader named as Abdelmalek El Gouri, also known as Khaled Abu Suleimane (sometimes spelt Selman).

Algerian news services, drawing on information provided by the security services, (i.e. the DRS), described Jund al-Khilafah as a “bloodthirsty” splinter group numbering less than 50, made up of remnants of Al Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), that operated in the maquis of Boumerdès, Tizi Ouzou and Bouïra. AQIM, like its predecessors, the Groupes Islamiques Armées (GIA) and Groupe Salafiste pour le Prédication et le Combat (GSPC), was known to have been well infiltrated by the DRS. El Gouri was reported by Algerian security sources as having been behind all the suicide attacks undertaken in the region between 2007 and 2011, since when the group is said to have been dwindling in number as a result of military action and low recruitment. El Gouri’s creation of Jund al-Khilafah was reported in the Algeria media as being an attempt to get back on to the national stage and win support from Salafist extremists.

From the outset, there were suspicions. Although entry into the Djurdjura is not officially forbidden, the Algerian authorities would normally strongly advise a foreigner not to enter the region because of the known risk of terrorism and kidnapping in the area. Gourdel’s visa application, in which he appears to have said he was going to trek in the Djurdjura, would have been forwarded to the Algerian authorities. He would almost certainly have been advised not to enter the region. If he persisted, then entry would probably have been made difficult for him, or possibly even forbidden by the local military. It would not be unheard of for a military escort to be provided. None of this appears to have happened.

Equally suspicious were that the kidnappers’ demands were out of keeping with all previous AQIM kidnap demands. Although this was ostensibly a new group, focusing on one immediate situation – French military attacks on IS in Iraq, my sources pointed out that these militants originated from GSPC/AQIM whose kidnap demands were nearly always multiple and always spread over a long period of time, usually many months.

A 24-hour warning was too short for France to make a decision regarding a change of policy in Iraq, especially at a time when the key political leaders were attending a UN meeting in New York. It was almost as if the group was deliberately not giving France enough time in which to respond.

Souaïdia’s evidence for DRS involvement in the Gourdel case, derived from his own contacts and sources, is much the same as that provided to me by the Rachad Movement. It lies in both the speed of transmission of the kidnappers’ videos and their content.

For instance, both Souaïdia and my Rachad sources, put forward a lot of technological evidence to explain that the kidnappers could not have broadcast their videos on the Web so quickly from their isolated location in the Djurdjura mountains, especially whenbroadband is so difficult to access in such remote parts of Algeria, without the help of an external agency, such as the DRS.

Souaïdia also raises the question of why the jihadists who killed Gourdel, as in other recent AQIM videos, covered their faces, unlike the jihadists of the 1990s. He suggests it is to hide their white arms and overweight bodies that indicate that they are not true jihadists (used to fighting in the open country) and that they now cover their faces to avoid recognition.

Souaïdia also raises a lot of technical issues about the locations where the videos were made, suggesting that they were stage-managed. For example, he points out that the third video shows the armed group being filmed with an array of heavy weapons, none of which appeared in the list of weaponry recovered later by the army.

These and other anomalies have been noted by several other analysts, notably those of the Rachad movement, suggesting that the videoed locations were not only contrived, but also possibly prepared before Gourdel’s abduction.

Another suspicion raised by several other sources is why it took the Algerians almost four months to find the decapitated remains of Gourdel’s body when they claim to have had some 2,000-3,000 troops combing the area.

Souaïdia suggests that the killing was a propaganda exercise to convince Algerians and the outside world that IS (Daesh) had established itself in Algeria. The problem now, eight months later, is that there is still no firm evidence of this.

While this view is widely believed by many Algerians, there is also another angle to it. This is that some Algerian sources believe that Gourdel’s kidnap and murder were designed to put pressure on the Algerian regime and its army to intervene in Libya. At the time, France was placing heavy pressure on Algeria to intervene military in Libya. Although the Algerian regime was divided on the question, the majority of the government and army were opposed to such action. If Gourdel’s murder was a “false-flag” operation, as Souaïdia and other sources suggest, it may have been undertaken by rogue elements within Algeria’s security apparatus, and perhaps also in France, to provide the regime with a pretext and legitimacy for “going into Libya” on the grounds that “ISIS is there”.

How the DRS prolonged their manipulation of Islamist violence

Souaïdia gives a long explanation of how the DRS managed to prolong its manipulation of Islamic violence long after the end of the civil war of the 1990s by using President Bouteflika’s “national reconciliation policy” to reinsert many of the released prisoners, still under DRS control, back into the terrorist circuit. Souaïdia claims that Abdelmalek El Gouri (a. k. a. Khaled Abu Suleimane), the supposed emir of Khakli (‘Soldiers of the Caliphate’), the IS group alleged to have killed Gourdel, and his deputy Othmane El-Assimi, belonged to this category of “released prisoners” that were subsequently “re-used” by the DRS

The DRS’s selection of prisoners was made carefully. According to Souaïdia, those known to have committed themselves to a change of life and peace were retained in prison. Those who had a radical profile or were willing to work with the DRS were released. One of the most famous of these was the infamous Abdelfatah Hamadache, known by DRS officers as the “honey pot”, because his radical speeches attracted young people “like bees to honey”. He was soon released, encouraged to found a radical movement and portrayed by the Algerian media as an Islamist leader when he was in fact a DRS agent.

Hostage-taking and the creation of new armed groups

There is much that could be said about hostage-taking and the DRS, not least that the official accounts of each incident raise more questions than answers. However, the point that Souaïdia makes is that before each hostage-taking, “security” journalists working for the Algerian press published disinformation provided by the DRS that announced the creation of a new armed group that stemmed from dissent within a previous group, without the corroboration of any other independent source of information.

Souaïdia cites the split of the GIA in 1997 to form the GSPC, which became AQIM in 2006, with further splits to form MUJAO in 2011 and Mokhtar ben Mokhtar’s “Signatories of Blood” in 2012. The most recent was the supposed split from AQIM in August 2014 to create Jund al-Khilafah. Souaïdia could also have mentioned Ansar al-Din, also in 2011, that was led by Iyad ag Ghali, known by many as the “DRS’s man in Mali”. Souaïdia might also have mentioned what is believed to be the genesis of a new split from Mokhtar ben Mokhtar’s “Signatories of Blood” or “Mourabitoune” as they are also known.

Souaïdia is technically incorrect if he is meaning that a new armed group is created before every single kidnap. But he is broadly correct if he means every new spate or phase of kidnapping.

In addition to Souaïdia’s comments, my own research has revealed that the leader of every armed group that has been involved in the taking of some 110 western hostages since 2002 (including In Amenas in 2013) has been associated with the DRS in the way that Souaïdia describes. Indeed, in some cases, what we might call “valuable” hostages, such as four of those kidnapped from Areva’s Arlit uranium mine in September 2010 and released on 29 October 2013, have been held captive in Algeria. This was almost certainly for their safety. However, RFI (Radio France International) unwittingly let the cat of the bag when it reported that local Malian Tuareg, with whom their reporters had been talking on the day of the hostages’ release, confirmed that the hostages had been held “just on the other side of the frontier in Algerian territory, to the north of Bourassa (Boughassa).” That area is an Algerian military zone.

Tension between the army and DRS

Between September 2013 and January 2014, the long battle within the Algerian regime, the so-called battle of the clans, between the presidency of Abdelaziz Bouteflika and General Mediène’s DRS seemed to come to a sudden and unexpected end with the Presidency, through the office of General Gaïd Salah, the Deputy Minister of defence and Chief of the General Staff, dismissing most of the DRS’s top Generals. By September 2013, Bouteflika, although severely weakened physically by a stroke in April 2013, had closely allied himself with army chief General Gaïd Salah, so much so that the restructuring of the DRS appeared to be a direct conflict between the army, under the command of Gaïd Salah, and the DRS.

Although DRS boss, General Mediène, has remained in post, albeit severely weakened, most of his top commanders, notably General M’henna Djebbar, Head of the Direction Centrale de la Sécurité de l’Armée (DCSA); General Athmane “Bashir” Tartag, Head of the Direction de la Sécurité Intérieure (DSI) and the Direction du Contre-espionnage (DCE); General Rachid “Attafi” Lallali, Head of the Documentation et de la Sécurité Extérieure (DDSE); and General Hassan (Hacène), whose proper name is Abdelkhader ait Ourabi, head of the DRS’s Special Intervention Forces, were “retired” or dismissed from office under one pretext or another. Many of DRS’s key departments were either closed down or transferred to the control of the army.

Most analysts believe that the pretext for this dramatic move by the presidency and army against the DRS was the DRS’s failures at In Amenas. Most analysts and commentators believe that the DRS was paying for price for its lapse in security. My own view, published in other ISCI articles, is because In Amenas was a DRS false-flag operation that went disastrously wrong. It this turned out to be extremely costly for Algeria, both economically in terms of lost revenues, and geopolitically.

While Souaïdia’s analysis of In Amenas is broadly similar to my own, he does add a dramatically new and immensely important dimension to our understanding of the nature and outcome of the battle between the Presidency and the DRS and what appears to be the continued role of the DRS in Algerian state terrorism subsequent to the In Amenas attack..

The role of the General Hassan and the DRS in the destabilisation of Tunisia

Souaïdia’s wholly new contribution to our understanding of contemporary Algeria stems from information given to him by his informants regarding General Hassan’s links with “emirs” acting under his orders in Tunisia.

Since the start of the “Arab Spring” in Tunisia in late-2010 and early-2011, there have been a stream of allegations about the involvement of Algeria’s DRS in trying to prevent the emergence of democratic governance in Tunisia and what Souaïdia calls the “democratic contagion of Algeria”, and of then trying to destabilise Tunisia’s fledging new government. But there has been no hard evidence: no smoking gun.

The latest such incident was the bloody attack on the Bardo museum in Tunis on 18 March. As with many other terrorist incidents in Tunisia, it was not long before it emerged that the leader of the attack was of Algerian origin. On 22 March, Tunisia’s new President, Beji Caid Essebsi, said, visibly upset, in an interview with the French TV channel I-Tele: “Whenever a terrorist group is flushed out in Tunisia, it has an Algerian leader.”

Tayeb Belaïz, Algeria’s Interior Minister at that time, responded immediately saying: “Terrorism has no nationality, no country, no religion, no colour and no humanism. It can manifest itself in any territory and I make no difference between terrorists whatever their name.”

However, Souaïdia suggests that one of those “names” is that of the DRS. In fact, Souaïdia says that he has been informed by many of his former colleagues that the leaders of some of the jihadist groups sowing terror in Tunisia “take their orders from Algiers.”

Souaïdia went on to say that following the military suppression of terrorist activity in Tunisia’s Mount Chaambi border area in 2013, the Tunisian army recovered the mobile phones and SIM cards from the bodies of several Algerian jihadists killed in the region. An analysis of the SIM cards by the Tunisian army revealed their communications with DRS officials in Algiers, including their phone numbers and even their nicknames.

If this information is correct, it is strong evidence of what has long been suspected, namely that Algeria’s DRS is bent on destabilising its neighbour, Tunisia, in the same way that it did Mali.

Most of the “terrorists” in the Mt Chaambi area are believed to have moved into the region after the French military flushed them out of Mali earlier in the year. There, they had mostly been part of AQIM, whose objective in Mali was to weaken the Tuareg rebels who had taken control of most of northern Mali (“Azawad”) and also destabilise Mali as part of an Algerian-backed Islamist insurgency. AQIM’s leader in the area, now dead, was Abdelhamid abou Zaïd, another DRS operative. AQIMs forces in Mali were supplied and supported by Algeria’s DRS, with food, fuel and, as we learnt in early 2014, arms belonging to Algeria’s army.

Souaïdia’s evidence from Tunisia throws a great of light on the bizarre situation in which General Hassan found himself in January-February 2014.

Souaïdia does not give us the date when the Tunisian army found the SIM card links between the Mt Chaambi fighters and the DRS, nor the date that the Tunisian authorities handed the evidence over to the US intelligence services, who, in turn are said by Souaïdia to have asked Algeria’s army chiefs to put a stop to this practice once and for all. The date would have been at some time in the latter part of 2013 and most likely close to the end of the year.

Hence Algeria’s creation in December 2013 of a “special security commission” under the control of General Gaïd Salah and the presidency in an attempt to get on top of those DRS officers who were in control of the information and intelligence on both corruption and security issues and who maintained suspect ties with the jihadists.

On 13 January 2014, official notification of Hassan’s “retirement” was posted. At that time, I did not know about General Hassan’s involvement in Tunisia.

Behind the scenes, a massive power struggle was brewing up. At some point in January, General Hassan was summonsed to answer extremely serious questions, or charges, before the military prosecutor. The charges against Hassan were: creating armed groups; retaining and withholding disclosure of weapons of war and making false statements of weaponry stocks used or placed at his disposition in the course of his exclusive prerogatives in the fight against terrorism. As Souaïdia said, such charges effectively amounted to treason.

What Souaïdia may not have known is that there was a technical basis for these charges. These were that Hassan was responsible for recovering the weaponry that the Algerian army had covertly supplied to the Islamist insurgencies in Mali and return it to its original army depots. However, as this was a secret operation and one that had to be kept completely under wraps, Hassan had to move the weaponry across Algeria without notifying the administration of each wilaya (province) being traversed, as is required by law.

When Hassan refused to respond to the summons, General Lakhdar, who had replaced General M’henna Djebbar in September, was sent to try and get him to co-operate, but he again refused. Then, on Wednesday 5 February, Gaïd Salah ordered the mobilisation of three sections of the Gendarmerie to arrest him. When Hassan refused to comply, the gendarmes broke down the door of his house and took him by force. On Friday 7 February, Hassan was ordered to appear before an investigative military judge in Blida.

On February 12, General Mediène’s DRS, or at least what remained of it, launched a devastating attack on General Gaïd Salah. The attack was in the form of an interview by retired General Hocine Benhadid in both the El Watan and El Khabar daily newspapers. The El Watan headline read: “Bouteflika must step down with dignity and Gaïd Salah is not credible.”

Benhadid – a former commander of the mythical 8th Armoured Division, adviser to former president Liamine Zeroual (1994-99), and one of the few Generals to resign (at the age of only 52 in 1996) – broke his ten-year silence to denounce what he called a “dangerous situation”.

In a brutal attack on Gaïd Salah, Benhadid said: “The Chief of Staff has no credibility, and no one is fond of him.”

Benhadid also called on Bouteflika to step down “with dignity” and not run for a fourth term in April (2014). He said someone who was “sick” and the “hostage of his entourage” could not guarantee the country’s stability.

The former General, who said he was speaking on behalf of others in the armed forces, but without saying whom, “because we cannot let this situation continue”, also accused the president’s inner circle of “treason” after Amar Saâdani, Secretary-General of the ruling FLN party, accused General Mediène of “interfering in politics to the detriment of the country’s security”.

In addition to his attack on Gaïd Salah, Benhadid also singled out Bouteflika’s brother Saïd Bouteflika for criticism, whom he described as the “main actor” in the presidential clan. In a direct reference to the involvement of the Bouteflika clan in the corruption that shrouds the regime, he accused Bouteflika’s entourage of “playing with Algeria’s destiny” in order to “save its skin, because corruption has reached dangerous levels”.

This was a demonstration of Generals coming to the defence of Mediène. Would we see Generals coming to the defence of Gaïd Salah? The answer is probably no. Benhadid’s statements immediately raised questions as to whether Generals might no longer accept Gaïd Salah as their supreme commander by perhaps resigning. His intervention even opened up questions as to whether it was the precursor of a possible, although unlikely, military coup d’état.

However, on that high point, with both parties seemingly going for the jugular, the fighting stopped. There were no more allegations and counter allegations, no more public attacks and damning disclosures by either side and nothing more has been heard of General Hassan’s trial. There was silence in the press and the charges against Hassan simply “disappeared”.

The re-emergence of the DRS

What happened?

Those were the events, and my analysis of them, as I knew them at the time. However, we now know, thanks to Souaïdia, that the President’s entourage, notably General Gaïd Salah, was in possession, presumably thanks to the Americans, of the DRS’s activities in Tunisia and General Hassan’s operational command of them.

Souaïdia believes that the restructuring of the DRS in 2013-2014 was also a consequence of the discovery of General Hassan’s links with “emirs” in Tunisia acting under his orders, as much as it was a consequence of the other reasons that I have put forward, notably In Amenas.

Souaïdia believes that Mediène, who was neither dismissed nor retired at that time, resisted this pressure on him from the presidency and Gaïd Salah and in February 2014 reached a compromise with them.

Indeed, one outcome of this compromise, according to Souaïdia, was that media attacks against the DRS stopped abruptly and no further action was taken against General Hassan. This explains what Souaïdia calls the “temporary” arrest of General Hassan.

The one clue that a deal had been done between the presidency, Gaïd Salah and Mediène was an article by Salima Tlemçani in El Watan on 13 February, the day after Benhadid’s attack.

Salima Tlemçani, whose real name is Zineb Oubouchou, although a professional and extremely able journalist, has had a close “working relationship” with the DRS since the 1990s, with the result that her articles often contain valuable insights into DRS thinking or “messaging”. In this particular article, although very difficult to interpret, there are indications that some sort of deal is in the offing.

Another outcome, as Souaïdia tells us, is that seven months later, in this poisonous atmosphere between Mediène and the army, Mediène’s officers “staked out their territory against the army chief of staff by kidnapping and murdering Hervé Gourdel. In so doing, they reminded the French authorities that in the ever-present struggle against terrorism, now represented by the Islamic State, the DRS is as indispensable to them as the Algerian army.”

If Souaïdia’s analysis is correct, and there is much corroborative evidence to suggest that it is, then Algeria and neighbouring countries, especially Tunisia, Mali and Niger, but also perhaps Mauritania and Morocco (and of course Libya) can expect more manipulation of “Islamic terrorism” in the same manner that Algerian state terrorism has held sway across the region for the past generation.

Endnotes

[1]Habib Souaïdia, La sale guerre. Le témoignage d’un ancient officier des forces spéciales de l’armée algérienne,1992-2000 (The Dirty War: The testimony of a former officer of the special forces of the Algerian army, 1992-2000″. Preface by Ferdinando Imposimato, La Decouverte, 2001, 203 pages.).

[2]Daniel Ben Simon, Ha’aretz (Israel) “I cannot remain silent”, Algeria-Watch, April 20, 2001. http://www.algeria-watch.org/farticle/sale_guerre/haaretz.htm

[3]An Enquiry into the Algerian Massacres. Hoggar Press, 1999, 1,473 pages, with Forewords by Professor Noam Chomsky and Lord Eric Avebury.

[4] This article was written a few days before the “terrorist” attack on Tunisia’s tourist resort of Sousse in which at least 27 tourists (possibly more) were killed. No changes have been made to the article in the light of that attack.